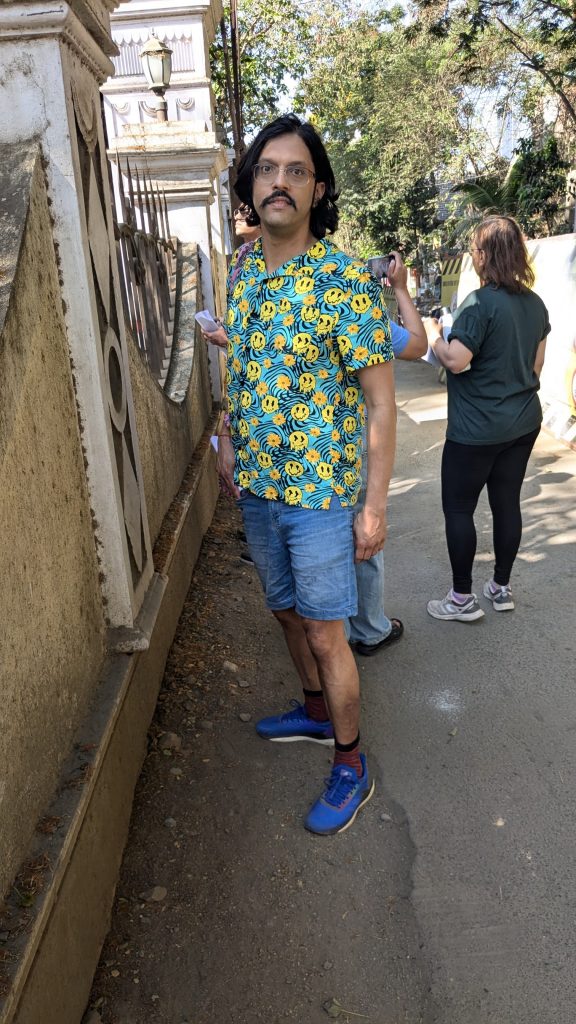

On my most recent trip back to my parents in India, I had the opportunity to visit some of the last standing abandoned textile mills in Parel, South Bombay. Scheduled for imminent demolition, with their passing part of Bombay’s hidden, working-class history will be lost forever.

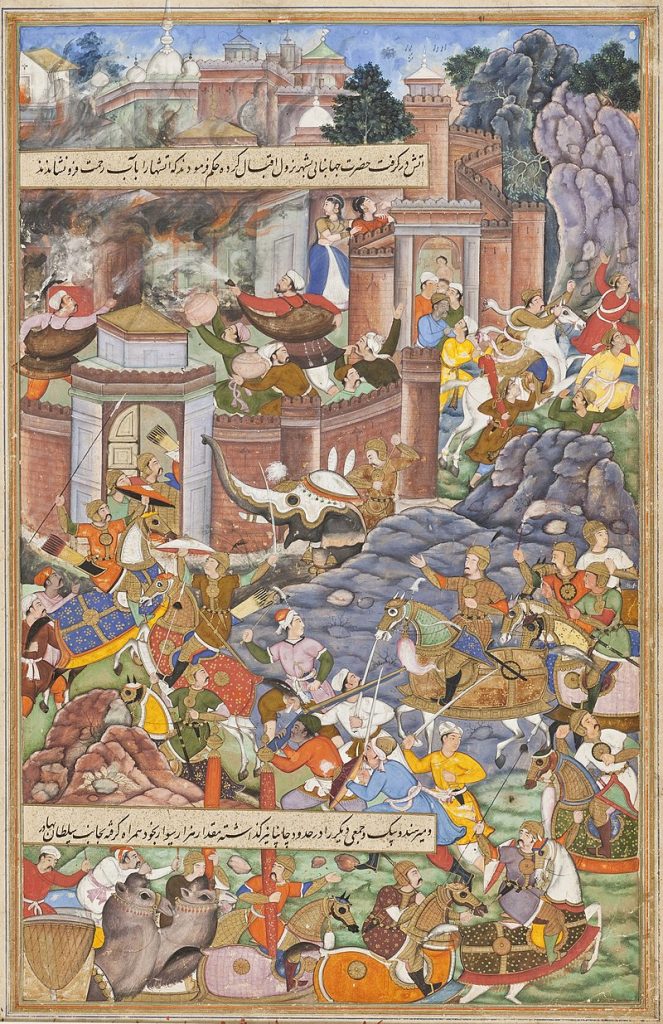

The shuttered mills, overgrown with trees and covered in dust. already have something of the aspect of the ancient fortresses which abound in this country. In a way, it is apt, as these were the sites of a battle of sorts. It was here, in these ruined places, that some of the most powerful and radical unions in the country- the textile workers unions – made their last stand. This was the legendary eighteen month general strike of 1982, which brought the powerful Bombay Mill Owners association to its knees and bought the commercial capital of India to a standstill.

From the 1860s through the 1980’s the textile industry had been at the heart of Bombay’s economy, and huge swathes of the now fashionable south Bombay had then been carpeted by almost 130 textile mills, known then as ‘Giringaon’ – literally, Mill Village. The vast barrack towns of workers that had sprung up around the mills had become a laboratory of left wing and radical politics even in the days before independence. The Communist Party of India had deep roots here, for that party’s founder Shripad Dange cut his teeth organising workers here, and founded one of Giringaos most left wing unions, the Girin Kamgar Union.. A variety of other radical groups, such as the armed anti-caste activists the Dalit Panthers, modelled explicitly on the Black Panthers, also found homes here. These groups were all finally crushed in 1983, by an alliance of mill owners and the government, in a process analogous to the crushing of the miners unions by Thatcher. Just like in England, their destruction paved the way for the rise of neoliberalism and right wing politics in Bombay.

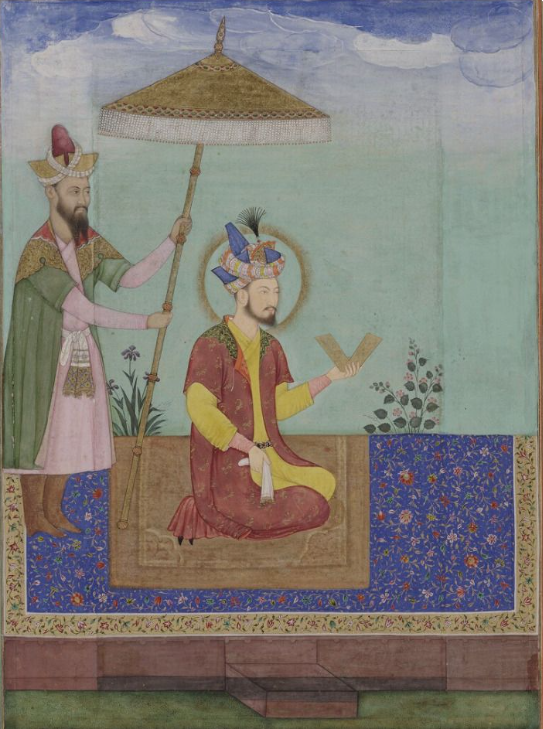

The spectre of Datta Samanth

Breaking the textile unions had not been easy, not least because they had a formidable opponent in the textile workers’ official spokesperson in the strike of 82 – the firebrand Dr. Datta Samant. As the popular refrain of the time had it, “on one word of Datta Samanth, all of Giringao shall come to a standstill.”

Datta Samanth, a veteran trade unionist, known variously as Doctor Saheb and The Burly Man of Ghatkopar, towers over the history of this time. He was quickly named the ringleader of the general strike by the government and the press, to his critics then and now either a power hungry conman who ‘tricked’ the working class into an unwinnable strike for personal political gain, or an obstinate zealot whose blind followers succeeded only in ensuring the destruction of the workers movement. This view however underestimates the well-documented militancy of the grassroots at the time and betrays something of an upper class Indian’s disdain of ‘easily misled’ and ‘naive’ labourers. The journalist Rajni Bakshi, who interviewed many of the striking workers throughout 82, captures the spirit of the times.

Source: whatshot.in

“On a bright spring morning [1982], I had first encountered the anger and superhuman determination of the textile workers in the dark hut of Lata Shelke. Lata’s husband, who worked in a nearby textile mill, sat cross-legged on the metal wire bed, which was the only piece of furniture in the one-room home. He talked with emotionally charged conviction about his boycott of the mill where he had spent all his working life. His neighbour, the fiery K.P.Kamble, had walked in and the conversation had soon taken a dramatic turn with his heated, impassioned tirade against the seth log [wealthy men] and neta log [politicians]. The blood ran hot then….The long awaited, bada kranti [great revolution]was at hand. “Let us kill all the big-wigs of old thoughts,” shouted Kamble to his friends, neighbours and sympathizers.”

“..a mother of five children, Lata seemed to do more than echo what was said around her. She did not share the fiery militancy of Kamble but displayed a quiet determination of her own and articulately explained why she stood behind her husband in his decision to strike. “There comes a time” Lata would say, “when you just have to fight (ladnaihich padega)”

A people’s history of Bombay

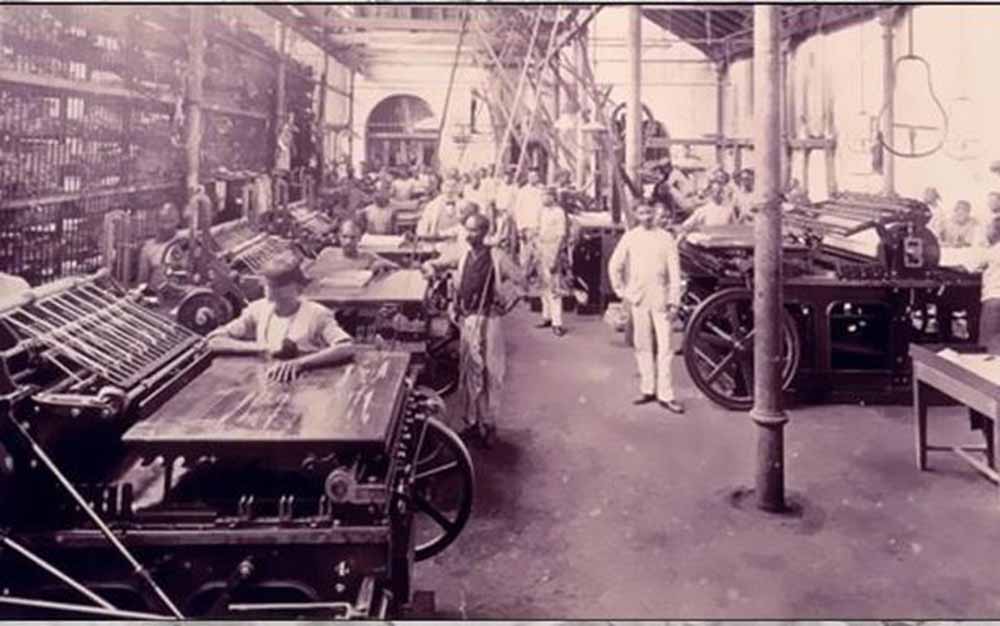

The story of the Bombay textile industry begins during the height of the British empire. It was the 1860s, and the great uprising of 1857 had long been suppressed. Bombay was an ordinary fort town, until events in- of all places – the United States of America forever changed its destiny. Until the 1860s, the slave plantations in the cotton belt of the American south supplied most of Britain’s cheap textiles. Then the civil war broke out, and the Confederacy cut off the cotton supply to Britain, in the hope that it would force the British to intervene on their side against Washington. This proved a backfire for them but a windfall for the textile merchants of Bombay who made a killing supplying cotton to London for the duration of the civil war and directly led to Bombay’s rise as one of India’s most prosperous cities. The powerful mill owners would become part of the fabric of the city, and mills sprung up all over Bombay, occupying most of the central corridor of the city by the time the 20th century rolled in. Each of these mills had compounds that stretched out over acres, and little townships sprung out around them, with hundreds of workers and their families living in the workers tenements called “chawls”.

Narayan Surve, the former textile worker turned revolutionary poet, writes:

“From the Sahyadris they came, these men, half-farmers still, in search fo work to fill their stomachs – and the number of their settlements grew apace. Money orders from Mumbai would keep home fires burning in the Konkan…After the Quit India Movement of 1942 large numbers began to come to Mumbai from the Deccan plateau..these men never snapped ties with the village. They were still bound to the soil. Their villages were still alive and well in their hearts. After 1960, this class, whom we can refer to as the proletariat, became the real backbone of the city; it was upon their labour that the city depended, the mills, the factories, the showrooms, all of it”

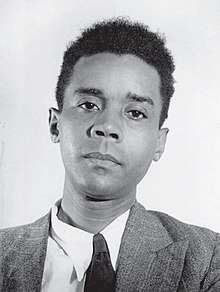

Even before the workers formed their first union in 1923, these labourers had a strong tradition of strikes and work stoppages. The British imperial authorities quickly grew alarmed at the spread of communist ideas among the textile workers and their suspicions were seemingly confirmed when an offshoot of the main union -Comrade Dange’s Giri Kamgar union – explicitly called themselves Marxist Leninist and staged two of the biggest general strikes in Bombay’s imperial history against proposed cuts to wages and the firing of union officials in 1928 and 1929. Dange himself was a notorious figure – who would go on to be convicted in the ‘Meerut conspiracy case’, in which the British government alleged a plot by Indian communists to violently overthrow the imperial government, with support from the Communist International. Dange was sentenced to twelve years for conspiring to “deprive the King Emperor of the sovereignty of British India, and for such purpose to use the methods and carry out the programme and plan of campaign outlined and ordained by the Communist International.” He was out in three years and went straight back into activism. Nehru and Gandhi may have been giants of the independence movement, but Comrade Dange had the ear of the workers.

The workers movement would not find many friends in post independence India. Though the ruling party, the, centre left Congress did hold some sway amongst workers in the heady days leading up to independence, this dropped off entirely by 1950, with the membership of the Marxist Leninist Giri Kamgar Union amongst the workers of Bombay exceeding the membership of Congress by 500%. The textile industry remained one of Bombay’s most strategic industries and needed to be brought under control. Congress moved quickly to designate an ‘official’ workers union – the NMMS, controlled entirely by Congress – and brought in strikebreaking laws which effectively criminalised most strikes. The labour courts refused to recognise any of the unions formed by the workers themselves, mandating that they join an official Congress union if they wanted their grievances to be discussed. The workers patiently fought their battles in the courts and in the streets.

Surve writes of his formative years growing up in the mills and the strong sense of identity amongst the workers

“I belonged to one of Mumbai’s many proud revolutionary worker families..On the eve of Dasshera, the mill workers decorate their machines. Everything is festooned with buntings, garlands made of flowers, balloons and flags. The entire department is decked up. That day, Aai would set me and my sister each on one hip and take us to her workplace. I would have a new shirt and cap embroidered with a gold thread…”

“When we got up in the morning and walked down the streets, the slogans we had chalked on the walls or the posters that had been pasted at night served as information. The posters and the walls were newspapers of the working class. They were also a barometer. “

Though it is true that the left wing unions had fragmented by the 1970s, it is a testament to the spirit of the union workers that they had endured at all despite a concerted effort by the government and the nine families who controlled all of the textile mills to destroy them. In 1974, however, it was clear that the aging Dange was losing his touch, infamously calling off a strike against a majority of the strikers wishes. Into this vacuum stepped Doctor Samant.

Enter Samanth

Source: telegraph.in

The great bane of the industrialists, Dr Samanth, was in fact a practising doctor and started his career running a clinic in Bombay’s suburb of Ghatkopar. He quickly found himself spending his time organising Ghatkopar housing association and slum tenants – many of whom were originally his patients – against exploitative slum landlords. He also became known for his campaigns against local corrupt politicians, a crusade that earned him not an insignificant amount of jail time . From here he would go on to defend quarry workers, and won significant concessions for them after a number of strikes, despite the strikers facing some brutal violence from both hired goons and the police.

HIs reputation rose to the point that he did spend some time in the 1970s in the Congress party on invitation from the left of the party- Congress after all was a centre left party and was a popular career move for once radical socialists and trade unionists. However, Samanth refused to be domesticated, spending the 70s representing factory workers in the industrial belt of Thane, on the outskirts of Bombay.

It was during his tenure as head of the factory workers union at a Godrej plant – one of India’s largest refrigeration companies – that he would cement his reputation as a ‘dangerous’ militant amongst Bombay’s middle class. For his tenure saw the Vikhroli riots – a violent clash between communist and socialist union workers affiliated with Samanth and activists for the rising right wing Hindu nationalist group the Shiv Sena, which left some dead. It was Samanth who was blamed for the violence, earning him another stint in prison. This earned him legendary status amongst Bombay workers, who regularly campaigned for his release. When he was released, he was a union representative for almost 300,000 workers. The rise of “Samanthism” was darkly discussed amongst the chattering classes, who went almost hysterical when they learned that employees of the Indian Express, one of India’s most venerable English language newspapers, had unionised under Samanth. Here were the unions coming for free speech!

An incident in 1979, where one of Bombay’s wealthiest industrialists, NP Godrej, his daughter and mother-in-law, were all stabbed by a disgruntled factory worker hours after Datta Samanth gave a thunderous speech in one of his factories didn’t help matters. He was now a serious problem for the Congress party, who disaffiliated with him and his supporters in 1980. He was detained under National security legislation, and it was only after a lengthy court case that the courts ruled that there wasn’t a sufficient nexus between Samanth and these incidents and freed him in 1982.

So when a delegation led by the veteran communist Salaskar approached Samanth to take up the cause of the textile workers in 1982, shortly after his release, they knew exactly what they wanted. His fearsome reputation was their last hope, the only thing which could make the mill owners listen.

Agneepareeksha – the trial by fire

The conditions in the textile mills in 1982 were dire. As the journalist Bakshi describes, most workers lived in dilapidated chawls where 15 to 30 men shared a room about 10 feet by 10 feet in size. Despite the mills generating enormous profits for the owners – less than 1% of the textile industries profits were reinvested in the improvements of working conditions. This led to what a World Bank report in 1975 called conditions of “abominable squalor” – the report went onto describe factories full of ancient machinery, broken floors, smashed windows, poor lighting and people living in what it described as an industrial slum. The number of industrial accidents went up every year, yet it was cheaper for the owners to replace the labourers than address working conditions. Chronic respiratory disease was endemic – any visitor to the mills would find cotton dust settling at the back of their throats, causing violent spasms of coughing within minutes. Against this backdrop, wages were kept so depressed that despite working from morning to night the average textile worker lived in unimaginable poverty.

source: counter currents.org

So it was that the textile workers united under Samanth and declared the beginning of the indefinite strike. Standing before a huge crowd of workers on 17 January 1982, under their red flag displaying their unions symbol – a fist protruding out of a factory chimney – Samanth declared “Continue your struggle peacefully but with grim determination until all demands are met. If I am arrested, do not heed any call to return to work that may be falsely issued in my name.”

The great strike had begun. The next day the spindles were silent, the chimneys blew no smoke. The mill owners predicted the strike would only last a month. But a month passed, and then another, and then another, until the strike stretched to a year. The mill owners began panicking. Police repression soon followed, with gatherings of more than five people in the mill areas now forbidden. It was reported that the mill owners would hand lists of troublemakers to the police, who would arrest them all and put them in lock up. Despite the ever present threat of hunger and homelessness, 250,000 textile workers in a show of solidarity refused to go to work for eighteen months.

In order to survive the workers banded together to organise mutual support committees and fundraising committees to the pay bills and debts of their members, and food distribution committees to provide them food. Thousands of workers returned to their villages to educate their people about their strike and stoke popular support. As one striker said “Workers are even eating half their normal food and living somehow and passing the time fighting for the future – now we are not scared.”

Narayan Surve, the textile-worker turned poet, wrote the poem ‘Four Words’ at the height of the strike – capturing the high passion of the times.

Four Words

The struggle for the daily bread is an everyday

Question

At times outside the gate, at times inside

I’m a worker, a flaming sword

Listen, you intellectuals! I’m going to commit a

Crime.

A little is seen, seen, risked,

There is also the smell of my world in it.

When I missed, missed, learned something new.

As I live I am in words

Always wanting more precious bread,

Bread, which is turned into the covered royal

Seal.

My hands of words hold flowers

My hands of words hold stones

I have not arrived alone, the epoch’s with me!

Beware! this is the beginning of the storm,

I’m a worker, a shining sword

Listen you intellectuals, a crime is about to happen

As the strike dragged on, there were some voices amongst the mill owners regarding coming to some kind of accommodation with the workers. Such was the momentum that the Congress’s Cabinet minister for commerce, Vishwnath Pratap Singh, agreed to meeting with Samanth in 1983 to reach terms. However the prime minister Indira Gandhi herself intervened to demand they take a firm line, and not negotiate with the workers. This militant working class movement, whose roots stretched all the way back into the nineteenth century, was too much of an impediment to the wave of neoliberal “modernisation’ that was sweeping not just India but the world. The scale of the movement spooked the government – Bombay had already been paralysed, and if the strike spread to the dock and port workers, Samanth would become one of the most powerful men in the commercial capital of India.

Aftermath

Ultimately, having preferred a year and a half long stalemate and catastrophic losses to negotiating with the workers, the mill owners took the unimaginable step of closing the mills forever. Although this would mean immense losses in the short run, in the long run this would mean cutting the heart out of the troublesome left wing union movement forever. For their part, though the workers knew it would be a difficult struggle, this outcome had been unimaginable.

The old Marxist Dange, now a happy grandfather and observer from the sidelines, would likely have observed that the workers had come up against the forces of history. The textile industry in Bombay no longer was as central to India’s economy (it only manufactured 30% of India’s textiles in 1982, as opposed to 85% in the early part of the 20th century), and many were already calling for replacing manufacturing with a services based economy.. Unlike most of his left wing colleagues, Dange was not overly enamoured of Dr Samanth, noting the good doctors disdain of Marxist theory in favour of simple, practical demands like wages and improvements in working conditions. Samanth, Dange believed, was no true socialist at all but an ‘anarcho-syndicalist’ – a person who believed they could capture the state by simply capturing one factory at a time – without a broader understanding of the economic and political forces at play, he said, this approach was doomed to fail. (Of course, many would detect some petulance in this ungenerous view of the current champion of the people by the former one.) A big what if in Bombay’s social history is what would have happened if Dange had not been too elderly, as he himself put it, to join forces with Samanth. It was Dange after all who masterminded the strikes of the 1920s which shook the British imperial government almost half a century before..

The mill owners either sold off the mill lands to private developers, or moved their operations outside Bombay to areas with less ‘troublesome’ workers. Most of the 250,000 striking workers found themselves unemployed and on the streets – those that went back to their old mill owners out of desperation had to sign ‘productivity’ agreements – accepting wage cuts and increased workloads, and of course, an understanding that they would be fired as soon as the bosses caught a whiff of organising or union activity.

A big beneficiary of the destruction of the left wing union movement was the right-wing Hindu party the Shiv Sena. The hatred between the communist and socialist textile workers and the Shiv Sena ran deep, as the Shiv Sainiks were built up during the strike years by the government to act as strikebeakers for the mill owners. After the strike, communists were removed one by one from their jobs, with one of the Giri Kamgar unions leaders Prakash Bagave who fought for his job back for 14 years, claiming that Indira Gandhi had paid the Shiv Sena more than 250,000 rupees to break the strikes. By the late 1980s, the Shiv Sena dominated the politics of the city. The collapse of the left union movement not only heralded the arrival of neoliberalism, but the rise of Hindu nationalism.

Many of the old mills were swiftly redeveloped into offices to house the new service industries that were destined to replace manufacturing as the future of Bombay – insurance, trading, investment banking and information technology. The rest were were either developed into high rise apartments, luxury malls or nightlife venues for those same service industry workers. Kamala mills, Shanti mills, Phoenix mills – today these names are still well known in Mumbai, but as shopping centres, cocktail bars, hipster pubs and venues for gigs.

In the morning of 16 January 1997, Dr Datta Samanth left his home in his car in the Powai district of Bombay when his path was suddenly blocked by a cyclist. When he lowered his window to find out what was going on, five unknown men approached his car. They fired seventeen bullets into his head, chest and stomach in broad daylight, before dropping two pistols and melting away into the city. So it was that the last great titan of the working class movement bled out onto the streets of the city he had spent his life defending.

My own home in what is now Mumbai is in an apartment complex built atop one of the demolished mills. It overlooks one of the last standing undeveloped mills, scheduled for imminent demolition. When it is gone, I wonder what will happen to the ghosts of those generations of working class families who toiled there, supplied so much of the revolutionary spirit and conscience of Mumbai. As bleak as the final outcome was, their relentless solidarity and optimism against impossibly powerful forces seems all too relevant for our current time.