PART I

Contact

Toulon, France, 1787. A large French merchant ship, the Roy L’Aurore, registered to one Monsieur Pierre Monneron , makes its way into the busy trading port. The dockworkers, used to seeing flags from all around the world, would nonetheless have frowned to see fluttering from its mast an utterly alien green standard. Arabic calligraphy announces that the ship belongs to the ruler of the Indian kingdom of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, the most hated enemy of the English in India.

The Toulon port officials would have been introduced by the ships captain Pierre Monneron to three bearded, olive skinned passengers in brocaded silk tunics, decked out in heavy necklaces of pearl and jewelled turbans with egret plumes. Accompanying them were was a retinue of fifty stony-faced olive and dark skinned men dressed up in similar fantastical clothes, bright and colourful under the grey French sky.

These, Monneron would have declared, were the royal ambassadors from the sultanate of Mysore – the nobleman Muhammad Dervish Khan, the octogenarian general Akbar Ali Khan and the soft spoken poet Mohammad Osman Khan. They had come bearing fabulous gifts from Tipu Sultan for the king Louis XVI of France – pearls, cotton robes and diamonds. The last gift was all the more precious in those days, when the worlds only known source of diamonds was the Golconda mines of Southern India.

They had also come with a proposal too, from their king. The great Tipu Sultan, Asad-allah-ul-ghalib, the Victorious Lion of God, was engaged in a life and death struggle with the English invader in India. Tipu Sultan knew about the ancient enmity of France and England, and remembered the days of his father the French had offered assistance against the British in India. They had come to persuade the king of France to take up arms again against their ancestral foes, and aid Tipu Sultan in his great crusade.

In return the French would be regarded as eternal friends of Mysore, ‘as long as the sun and moon shall endure’. Her traders would be the only Europeans allowed into the South Indian kingdom, and French possessions in Southern India would be granted Mysore’s protection.

Though, which God forbid , the earth and the skies should be taken from their places, yet shall not our mutual friendship be impaired.

This was the first formal embassy of any kind by an Indian ruler to a capital of Europe. It was an expensive gambit by Tipu. The representatives of the French in India had in truth proved reluctant allies to Tipu’s father, and had dragged their feet about entering Tipu’s war against the English. Tipu solution was therefore to cut out the middleman and approach the French king directly, so that they could deal sovereign to sovereign.

On June 25, 1787, the Indian diplomats would enter Paris on their way to Versailles. Their gifts were displayed prominently in a public exhibition in the city, sparking a fierce debate about France’s overseas adventuring – the kingdom, as it would turn out, was in a financial crisis, a state of affairs not helped by France’s recent intervention in the American revolutionary war. Tipu Sultan’s ambassadors nonetheless caused quite a stir in the Parisian social scene. The Journal de Paris published almost daily updates on their whereabouts. The exotic politicians were the must have dinner party guests for any fashionable aristocrat living in the city. They lodged in expensive hotels in the Saint Cloud district of Paris, spent lavishly in her restaurants and frequented her operas. They would end up staying almost a year. Mohammed Dervish Khan spent the year obsessively recruiting watchmakers, gunmakers and glass blowers to take back with him to India, while Akbar Ali Khan, despite his age, was rumoured to be carrying on an affair with the daughters of one of the King’s Swiss Guards.

Madame Le Brun, Marie Antoinette’s favourite painter and perhaps the most famous woman painter of the 18th century, had Dervish Khan sit for her at her own request. The rare monumental oil painting that arose out of these sittings, of Dervish Khan in his muslin white fabrics, posing with his hand upon his dagger, was displayed in the Paris Salon of 1789 to critical acclaim.

In August 1788 the ambassadors were finally granted an audience with Louis XVI. Though sympathetic, Louis XVI could not help. France was rapidly descending into a crisis of her own making. The moral legitimacy of the most conservative absolute monarchy in Western Europe was being challenged by the new ideas of the enlightenment engulfing the continent. Attempts to modernise the administration and economy to release them from the stranglehold of the nobility had been fiercely resisted by an aristocracy jealous of their ancient privileges. Mere days after the reception of Tipu’s ambassadors, the kings finance minister Brienne would resign, after informing Louis XVI that France was officially bankrupt and unable to meet her interest repayments on the national debt. The price of bread, the staple of the French peasant, had skyrocketed so that it took up 60 to 90 percent of the average labourers monthly wage, and grain riots had paralysed the kingdom. Just as the embassy itself had been a desperate gambit by Tipu, the pomp and pageantry of the royal reception had in fact been nothing more than a last attempt by Louis XVI to show his people he still retained the glamour and majesty of his ancient house.

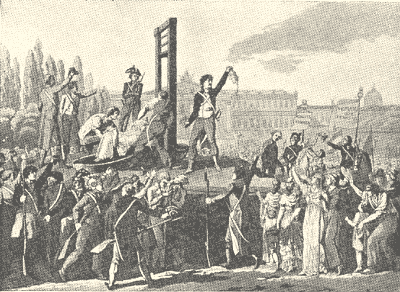

The embassy would be frustrated and the nobles would return from Versailles empty handed. The Indian ambassadors fell out of favour back in Mysore and Mohammed Dervish Khan would eventually be beheaded by an irritated Tipu Sultan. The hapless Louis VXIs own journey to the guillotine would also soon be beginning. In July 1789, a Parisian mob would surround and storm the fortress of the Bastille, detonating a powder keg that would change forever the destiny of Europe. The French Revolution had begun.

The effects of what would be one of the first truly global revolutions would open up new opportunities in Tipu’s struggle. But before we get into the story of how the story of revolutionary France intersects with Tipu’s struggle, I shall take a bit of a detour into the history of the man himself – Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore.

Part II

Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan had been making a name for himself since 1767, when as a seventeen year old prince under the command of his father Hyder Ali, he had led a daring raid into the British city of Madras, burning down the Georgian mansions of the East India Company officials and almost abducting the Governor. In 1780 Tipu would fully explode into British consciousness when, at the head of one of Hyder’s armies, he completely annihilated the largest East India Company army in South India, in the battle of Pollilur in modern Tamil Nadu. Fifty of the English officers were taken captive, including its commander, the Colonel George Bailie, who has presented to Hyder Ali by Tipu strapped to a gun carriage.

Over the next few months, as Tipu seemingly won battle after battle, the British would lose control over much of their possessions in South India. Lord Macartney, reflecting on these disasters, remarked ‘the Indians have less terror of our arms, we, less contempt for their opposition. Our future advantages therefore are not to be calculated by our past exploits.’ Such was the scale of Tipu’s victories that by the end of 1780, the historian William Dalrymple estimates that as many as one in five of all the English soldiers in India were being held prisoner by Tipu in his sophistiscated fortress in Seringipatam, in modern day Karnataka in south India.

In Tipu the British had encountered a new kind of native threat – a ruler with a strong desire to create an modern industrial state. Fascinated by modern science ever since he had apocryphally peered through a microscope as a boy, Tipu knew that the feudal ways of old India were gone and understood that power now lay in mastery of this new world of machines and international trade. To this end, he sent not only the first ever Indian embassy to a European capital, described above, but had his diplomats establish Mysorean trading posts as far as Karachi, Oman, Baghdad and Constantinople. His ambassadors to China brought back silkworms that he used to develop a sericulture industry in Mysore, from which the region continues to benefit today. It was on Tipu’s orders that Dervish Khan had spent so much time recruiting watchmakers and glass blowers in Paris. He was determined that Mysore be self-sufficient in the production of gunpowder, and his gunpowder factories were full of modern industrial age innovations. The traveller Jan Lucassen describes Tipu’s gunpowder factory at Ichapur as having a migrant workforce drawn from all over India, workers organisations for collective bargaining , a pension scheme and even a compensation programme for victims of workplace accidents.

The employment of European mercenaries and soldiers by Indian kingdoms was not uncommon in the eighteenth century – in addition to the European trading companies, India was awash in European adventurers and soldiers of fortune. Tipu’s contemporary the Mughal emperor Shah Alam, for example, employed the French sellsword Jean Law as one of his most senior commanders. Tipu’s enemy the Maratha king Daulat Rao Shinde had an entire French batallion under the command of the debonair Savoy general Comte Benoît de Boigne, a royalist refugee. Characters such as the Irish mercenary Michael Finglas, better known by his title Nawab Khoon Khar Jung (literally, ‘Blood-drinking lord of War’) with his private mercenary army of 5000 up for sale to the highest bidder – or Gottlieb Koine, a German Jewish soldier of fortune who started his own dynasty with a Mughal princess, fathering the famous Urdu poet Farasu, were everywhere.

However, for Tipu, recruiting top talent from amongst these lot became an obsession. He used the wealth of Mysore to employ European engineers and European soldiers, mainly French, to reorganise the Mysoerean military among western European lines.

In Pollilur, then, British soldiers used to defeating native armies twenty times their size suddenly encountered well-drilled armies equipped with the latest in military technology. According to the author William Dalrymple, “Tipu’s [sepoys] rifles and cannons were based on the latest French designs, and their artillery had a heavier bore and longer range than anything possessed by the Company’s armies…In many repsects they were even more technologically advanced than the Companies armies,firing rockets from their camel cavalry. The defences of [Tipu’s] fortress at Seringipatnam was designed by French engineers on the latest scientific principles, following Sebastian de Vauban’s research into artillery resistant fortification designs.” Colonel Bailie would recollect his men being subject to the ‘hottest cannonade ever known in India’ in Pollilur, interspersed with missiles from Tipu’s camel rocket cavalry. Finally, accompanied the wailing of the nageshwaram – traditional Tamil oboes – and the beating of kettle drums, his men would be set upon by Tipu’s red coated troops ‘like waves of an angry sea’.

It was the English who would eventually have to sue for peace with Tipu, three years after Pollilur, on humilating terms. Faced with the complete reversal of their fortunes in India, and nearly bankrupted by war, the East India Company propaganda machine went into overdrive. Sensationalistic stories of torture and forced conversions to Islam of the English POWS in Tipu’s dungeons were breathlessly reprinted in the British press. Humiliatingly, it was reported that as an entertrainment for the Indians captured British soldiers were made to wear women’s dresses, ghagra-cholis, and dance before the natives. Tipu was portrayed as an unhinged despot whose implacable ‘hatred of Europeans’ was matched only by his oppression of his own subjects, particularly his Hindu ones. The ‘furious fanatic’ and ‘intolerant bigot’, who had “perpetually on his tongue the projects of jihad’, posed, with his modern European style army, a threat not only to the English but all the kingdoms of India. The whole project to unseat him took on the flavour of that particular species of liberal English imperialism that masquerades as humanitarian intervention. .

The British took up the cause of the Hindu Wodeyar dynasty, the ancestral rulers of Mysore whom Tipu’s father had overthrown in a coup, and encouraged Hindu rebellions throughout Mysore. They began to prise apart the delicate alliance that existed between Tipu and his Hindu neighbours, the Maratha Confederacy, not particularily difficult as the ancient enemies had only recently reconciled. Tipu certainly did have a reputation of being merciless and even cruel to his enemies, and it would not have been hard for the British to point to slaughters of Hindu or Christian rivals as evidence of some religious crusade. The charge that he was a religious bigot, however, was ridiculous. His prime minister Purnaiya was Hindu, as were many of his senior ministers. Despite being a devout Sunni Muslim he was a generous patron of dozens of temples, enjoying particularily close relationshipn with the Srinegeri Math temple, whose head priest he lovingly referred to as jagadguru, the ‘Guru of the world’, the Ragunatha temple, that operated just in front of his palace, and the Nanjudehswara temple,to whom he donated a priceless jade Shiva lingam. Nonetheless, the campaign was so effective that Hindu nationalists even today campaign to have Tipu’s name struck out from the history textbooks as an anti-Hindu bigot.

Over the next ten years, the British would build an impressive alliance against Tipu, which included the two most powerful kingdoms in South India, that of the Marathas and the Shia Nizams of Hyderabad, and a host of smaller kingdoms, who were wary of Tipu’s increasing power. It was in this desperate context that Tipu had sent his failed embassy to Paris. Two further attempts to seek French assistance also ended in failure as France convulsed with the Revolution. Tipu had no choice but to settle down for a fierce resistance which earned him a reputation even amongst his enemies as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’.

And then, all of a sudden, the world turned again. In 1792, in revolutionary France, a radical faction of ultra-egalitarian revolutionaries known as the ‘Jacobins’ seized power from the gentleman liberals and reformist nobles who had dominated the early days of the Revolution. They had a new plan and a new vision for the future. One of the Jacobin government’s first moves was to declare war on England and Holland. Out of nowhere, Tipu’s spies brought him the news that French warships had begun mobilising against the English off the coasts of South India.

A new, odd sort of French soldier would begin to offer their services to Tipu, red capped idealists preaching of liberty and of ‘the great revolution’. In 1794, the first republican revolutionary organisation in India, the Jacobin Club of Mysore, would be founded by this sort in Tipu’s fortress of Seringipatnam.

But who were the Jacobin Club, and how had they come to be involved with Tipu? Before we continue this story, we need to turn back a few years to the events of the French Revolution.

PART III

The French Revolution

‘The words that we have spoken shall never be forgotten on this Earth’

– St Just. Jacobin revolutionary

Very soon after Louis XVI was effectively deposed from power in 1789, rifts appeared amongst the revolutionaries about the future of France. The moderate liberal faction did not believe in completely giving up on tradition and abandoning all social heirarchies. Absolute power of the king was out, but instead of doing away with the French monarchical system, it would be reformed as it had in England, replaced by a modern constitutional monarchy where the king remained the ‘father of the nation’ but a legislative assembly exercised all the power. There would be democracy, but in the oligarchic mould of the ‘democracies’ of England and the United States, where only rich land owning men would have the right to vote. The economy would be liberalised, freed from the royal hand and delivered to the the invisible hand of the free market. The church would be reformed but France would remain Catholic.

On the other hand the radical faction coalesced around a social club known as the Jacobin club. ‘Jacobins’ believed in absurd things which appalled the more moderate revolutionaries – voting rights for all men, a secular state, the complete liquidation of the monarchy, the abolishment of all noble land and titles, redistribution of aristocrat wealth and a centralised, controlled economy managed by revolutionary committees. The most radical amongst them even called for extending the ‘rights of man’ to women and to people of colour– ideas anathema not only to most French revolutionaries but to all thinking men of eighteenth century Europe.

The Jacobins lost no time at all in putting their radical plans in motion once they seized power in 1792. They executed the king and queen and proclaimed the end of the royal line: henceforth France would be a republic. They abolished slavery throughout the French Empire, proclaimed universal suffrage and set in motion a massive programme of wealth redistribution from the lands and wealth they siezed from the aristocracy. However, their ascendancy coincided with a fierce royalist counter-revolution in the Vendee, which the Jacobins believed was being financed by foreign forces. Faced with war and obsessed by the prospect of counter-revolution, an increasingly paranoid Jacobin leadership set about purging France of every last trace of ‘royalism’. They demanded the heads of not only all the old royal officials and artistocrat families, but anyone accused of having of ‘royalist sympathies’, which came to include in time many of their colleagues who for one reason or the other ran afoul of the leadership. In one year, about 17,000 suspected royalists were guillotined in public squares throughout France – a period now infamous as ‘The Great Terror’. The Jacobin thinker St Just sums up the mood of the time

“Soon the enlightened nations will put on trial all those who have hitherto ruled over them.

The Kings shall flee into the deserts, into the company of the wild beasts whom they resemble,

and Nature shall resume her rights’.

After the Terror, it was inevitable that the flame of Jacobinism would be snuffed out. After just over a year in power, they were overthrown by a moderate faction known as ‘The Directory’. The Directory would unleash their own, less well publicised campaign of summary executions against the radicals, outlawing Jacobinism in the new Republic. But as much as the liberal moderates of the Directory touted the possibility of another Terror as justifying the criminalisation of Jacobin thought , it was the radical egalitarianism of Jacobinism that posed a greater threat to the oligarchs of Europe. Already, Haitian freedom fighters calling for independence from the French were reading banned Jacobin books and quoting Jacobin revolutionaries. Jacobinism, with its promise of both emancipation and revolutionary terror, came to occupy the space in the popular imagination that Maoism and Stalinism occupy in Western Society today.

So it cannot have pleased British intelligence, always sensitive to the threat of class war, to learn that Tipu Sultan had allowed his French soldiers to start a Jacobin club at Mysore, aimed at promoting the principles of ‘revolutionary Jacobinism’ in India.

PART IV

TIPU AND THE JACOBINS

With the overthrow of Jacobinism in the mother country, the ranks of the French adventurers and mercenaries in India were suddenly swelled by Jacobin orphans keen to export their lost cause to the wider world. The cause of ‘Le Grand Tippu Sultan’ and his stubborn resistance to the English attained some glamour to these idealists and Tipu was only happy to oblige any assistance from this unlooked for quarter.

Tipu personally oversaw the opening of the Jacobin club of Mysore – an affair that had included a special 2,300 gun salute, the launching of 500 rockets, and the planting of a Liberty Tree. East India Company spies reported that Tipu himself had been inducted into the Jacobin club, had been seen in public wearing the French revolutionary cockade and had been cheered in the Jacobin club as ‘Citizen Tipoo’. The new republics tricolour was hoisted within Tipu’s walls and the Declaration of the Rights of Man proclaimed at Mysore.

‘Death to all the Kings of the World, except Citizen Tipoo’

In 1797 the situation escalated. A rogue Jacobin navy captain named Francis Ripauld sailed into Mysore and promised the services of himself and his men to Tipu to assist the sultan in his “resistance to the British encroachments in South India”. He spoke of an entire French fleet loyal to the true principles of the Revolution stationed at Mauritius, who would surely be persuaded to join Tipu’s cause if he sent them an embassy. Tipu was delighted and gave Ripuald his blessing to act in his name. Ripauld returned to Mauritius along with Tipu’s envoy Abdur Rahim and set about raising an expedition to travel back with him to Mysore.

Ripauld in fact had no authority to speak for the Directory and the admiral in charge of the fleet at Mauritius had no intention of committing the French navy to assisting an outlaw Jacobin and a Mohammedan Sultan. However when he communicated the absurd request to his superiors, orders came from up top for him to assist Ripauld and Tipu in any way he could. The order came not from the Directory but from an up and coming general who was fast becoming a power unto himself in revolutionary France. This general was called Napoleon Bonaparte, and he was very, very interested in what Tipu had to say.

Napoleon had long dreamed of restoring French interests overseas, and perceived the formidable threat England would pose should the riches of India fall into her lap. Years before he had proposed to the Directory a fantastical campaign in the far east, where he would capture Egypt and Syria. This would allow him to control all the sea routes to the Orient. He would then lead an army into southern India to fight the English there. He disdained the East India Company as as society of ineffectual merchants, and assured his superiors that the ‘touch of a good French sword’ was all that was needed to collapse ‘the mercantile empire’ of the English. The Directory had been uninterested, but after Napoleon won a series of spectacular victories in Italy, they began to fear his influence and were all too happy to have him as far away from Paris as possible.

Napoleon’s army conquered both Egypt and Syria easily. No sooner had he subdued Egypt did news reach Napoleon in Alexandria of Ripauld and Abdur Rahim in Mauritius, asking for French assistance to drive the British out of South India.

In 1798, Napoleon would write personally to Tipu Sultan,

“To the most magnificent Sultan, our greatest friend Tipoo Sahib,

You have already been informed of my arrival on the borders of the Red Sea, with an innumerable and invincible Army, full of the desire of delivering you from the iron yoke of England..I would ask that you send some person to Suez or Cairo, bearing your confidences, in whom I may confer. May the Almighty increase your power and destroy your enemies

Yours C & C,

Napoleon Bonaparte

Frances Ripauld would suddenly be granted the expedition. In 1798 he and Abdur Rahim sailed back into Mysore at the head of an army of French volunteers. They were hailed as heroes and given a robe of honour by Tipu Sultan.

Napoleon’s letter, the culmination of all Tipu’s efforts for French intervention, would ultimately be the thing that sealed Tipu’s fate. English intelligence intercepted the letter. The Tory Governor General of India, Lord Wellesley, had long been fighting with the board of the East India Company to commit more resources to eliminating the threat of Tipu Sultan. Now he wrote to his superiors that the battle against Tipu had attained the character of a national emergency, with implications in the war against France. This was enough for the directors of the Company to persuade their friends in Parliament to shake the magic money tree. Lord Wellesley was granted all the resources he needed. An army of 50,000 men under the command of his younger brother, Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, was sent out to Seringaptnam to end once and for all the threat of Tipu. Their Maratha and Hyderabadi allies joined him, and in 1799 a great siege of Tipu’s fortress would begin by these three armies.

Meanwhile Napoleon would suffer the first major catastrophe of his career in Egypt. An English fleet under the command of the swashbuckling Horatio Nelson would surprise Napoleon’s ships in Acre in modern day Israel and utterly decimate his fleet. Napoleon would be recalled to France the next year. He would never again return to the Far East.

Friendless, Tipu would hold out for a nine month long last stand in the siege of his capital Seringapatam. The Jacobin volunteers fought with him to the end. At one point in the siege of Seringapatam observers would have witnessed the odd sight of Tipu’s French revolutionaries fighting the Marathas’ royalist French mercenaries, one French army flying the fleur de lys banner of Louis XVI, the other bearing the revolutionary tricolour, both clashing under an Indian sky amongst jostling Indian armies

By the end of the year, the English armies breached Tipu’s walls. Seirngapatnam was burnt to the ground, and Tipu sultan’s body was found hacked to death amongst the fortresses defenders. Amongst the effects stripped from the modernising sultan’s person would have been his favourite Swiss pocket watch, without which he was never seen in public.

The battle marked a major turning point for the British in India. It also sparked the realisation amongst Wellesley and his lot that as long as there remained any powerful independent kingdoms in India, they could not be trusted not to deal with the enemies of the English. The English had already noticed how the Marathas had been slow to send their army, how they had been watching carefully to see how the alliance with the French would work out for Tipu. The next fifty years would see fierce battles waged on the flimsiest of pretexts by the English against all the great powers of India, beginning with the Marathas. Arthur Wellesley’s meteoric rise to the prime ministership of Great Britain would begin the day Serangipatnam fell – he would of course go onto defeat Napoleon as well, in Waterloo, fifteen years later.

The episode stands as a testament both to uniquely global nature of the French revolution and to global vision of Tipu Sultan. Had Tipu succeeded in his plan, it would have changed the history of the British empire, which may never even have come into being without India. By extension it would have changed our modern world, born out of the British Empire’s collapse.

For a brief moment, then, Tipu and the French revolutionaries had stood on the precipice of an entirely new world.