courtesan turned revolutionary

nicknamed the ‘Amazon of Liberty’

On the morning 5th of October, 1789, a young Parisian market woman started banging a drum around La Halle in the fauborg Sant-Antoine in Paris. Her complaint, about the price of bread, was hardly an uncommon refrain that year. The starving city had seen almost daily riots about bread, and there was not a bakery in the city that was not under armed guard. What was uncommon was what happened next. By mid-day, about two thousand women had gathered to answer her call. ‘Your children are dying of hunger; if your husbands are perverted and cowardly enough not to want to look for bread for them, then the only thing left for you to do is to slit their throats.’ The two thousand women resolved to march on City Hall to demand the mayor answer for letting Paris starve. Their journey would take them all the way to the royal palace at Versailles, an audience with the King Louis XVI and one of the most dramatic episodes of the French Revolution.

On the Revolution

The great historian Hobsbawn once observed ‘If the economy of the nineteenth century world was formed mainly under the influence of the British Industrial Revolution, its politics and ideology were formed mainly by the French. Britain provided the model for its railways and factories…but France made its revolutions and gave them their ideas.’

It was in the crucible of the French Revolution that both liberalism and socialism in their modern senses were born. Even if now the traditional Marxist analysis of the Revolution as a bourgeois liberal revolution is being challenged, it cannot be denied that when the dust settled its main benefactors were the men of the new liberal capitalist class, typified by their champion the Marquis Lafayette, a liberal reformist aristocrat. The great triumph of these monied gentlemen was the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen’ in 1789. ‘All men are born and remain free and equal in rights’ these words ended the entire basis of feudalism and overthrew Europe’s most traditional aristocracy, who had only yesterday seemed invulnerable to the reforms spreading through Europe. It also allowed the new ‘middle class’ of bankers, merchants and wealthy traders access to the great offices of state traditionally reserved for the aristocracy.

However this victory was only made possible by a temporary alliance of the liberal gentlemen with those urban labouring classes whose aims were those espoused by the Jacobins during their brief and tumultuous ascendancy in Paris in their decidedly more radical egalitarian ‘constitution of 1793’ – which included amongst other things the unprecedented demand for universal male suffrage and the redistribution of wealth. Before the revolution in Moscow in 1917, the Jacobin Insurrectionary Commune was ‘the Revolution’ to which radical socialists in nineteenth century Europe aspired . Like Hobsbawn would observe, every revolution in Europe prior to 1917 aspired either to the principles of 89 or the more ‘incendiary’ ones of 93. As we shall see, it was working class market women who were key to bringing about the radical phase of 93.

The revolutionnaires

This historical era generally is not lacking in remarkable women. There was the giant of the liberal movement, the progressive aristocrat Madame Germaine De Stahl, whose salons in the early years of the revolution were the meeting place of the ages greatest philosophers and thinkers and the centre of all its early intrigues (‘Go hence to Madame de Stahl’s’ wrote the US ambassador to Paris in 1791 in his private journal ‘I meet here all the world’). There was the liberal intellectual Madame Manon Roland, one of the first to call for the overthrow of the king (Mme Roland: ‘I had hated kings since I was a child and I could never witness without an involuntary shudder the spectacle of a man abasing himself in front of another man). Though she was destined to fatally fall out with the insurrectionary commune over her belief in free markets and federalism as the basis of the new Republic, Mme Roland’s immediate circle dominated the politics of the early years of the Revolution.

On the left you had Pauline Leon, a chocolate maker who participated in the storming of the Bastille and who came to be associated with a faction disparagingly called the enrages, the angered ones, so radical they considered Robespierre as ‘too soft’ on the aristocracy. A tomboy fond of sporting her red cap of liberty with a sword and two pistols tucked in her belt, Pauline Leon was a regular sight at the meetings of the National Convention where she would heckle and harangue the liberals she so detested.

Her closest friend and fellow enrage was the actress Claire Lacombe, with whom she would found the society of Revolutionary Republican Women. Their patrols of pike, sword and pistol bearing all female volunteers were the terror of the respectable classes of Paris. (A troupe of furies, avid on carnage, as one opponent described them.) Lacombe herself had been in the very front lines of the fighting in the insurrection that established the Insurrectionary Commune. She was shot through the arm while storming the royal palace of Tulierres, and kept on fighting nonetheless, earning her the sobriquet the ‘heroine of August tenth’.

It was Leon and Lacombe who would articulate ideas which only existed on the most extreme fringes of the left– that of women’s complete political emancipation. In this, sadly, they would prove too far ahead of her time, horrifying even their left wing Jacobin colleagues who tripped over themselves to distance themselves from the project of womens political emancipation – women in France would only get the right to vote in 1944.

But beyond all these famous names, it is working class Parisian market women who are responsible for the urban working class uprising that followed the end of the liberal phase in 1789. After the abolishing of feudalism and the declaration of a constitutional monarchy in the dramatic summer of 89, executive power seemingly passed overnight from the autocratic King to the newly created National Assembly. Little would change however for the ordinary men and women who had propelled this new government to power, and Paris continued to be convulsed throughout August and September 89 by almost daily demonstrations by labourers, artisans and bakers. The National Assembly came to be dominated by a conservative faction led by Mounier, keen on ensuring the new voting rights be extended only to men of wealth and the king be preserved as head of state with a royal veto over all legislation. The King himself was refusing to sign decrees abolishing noble privileges and the Rights of Man, and ominously gathering troops around his palace of Versailles. With regulation of the market relaxed due to the liberals cherished commitment to the free market, the price of bread skyrocketed, prompting the rabble rousing journalist Marat to write about their betrayal ‘today, the horrors of dearth are felt once more, the bakeries are under siege, the people are short of bread, and it is after the richest harvest. Can there be any doubt we are surrounded by traitors who consummated our ruin?’ Demonstrations were met with repression indistinguishable from the autocracy of Louis XVI. (Mirabeau – The people are crying for bread – what monster answers this with gunshots?’) As Michelet says ‘Nobody felt all this more deeply than women. The most extreme sufferings had falled cruelly on the family hearth.’

And so it all came to a head on October 5, 1789. The two thousand women answered the banging of the young market girls alarm drum. They marched to the Hotel De Ville (‘City Hall’) of Paris, loudly shouting for bread. The Hotel De Ville was surrounded by mounted cavalry and infantry of the National Guard. Undetterred, the ‘housewives of Paris’ charged them , armed only with stones. The order went out to shoot, but the National Guardsmen firmly told their commanders they would not fire on the women. So they simply melted away before the women’s charge.

Forcing the door with pickaxes, hammers and hatchets, the women broke into the Hotel De Ville and ejected every man from the building. ‘Men were cowards.’ they declared ‘They (the women) would show them what courage was.’ As the historian Lucy Moore says “this violent appropriation of previously proscribed places was the first delight of the revolution..walking at ease where one was once forbidden to enter..for women, restricted by their gender as well as status, these new liberties were all the more potent.’ Men were deliberately barred from the occupation of the Hotel De Ville, as “they had failed as providers and as administrators.”

The women then armed themselves with weapons ransacked from the Hotel De Ville, including four cannons. Realising that there was little the hapless gentlemen of the Paris government could do, they decided to go visit the ‘Baker’ in Versailles – the King – and present their petition to the National Assembly themselves. An eyewitness testimony reads , ‘In the middle of the Champs Elysées, …he saw detachments of women coming up from every direction, armed with broomsticks, lances, pitchforks, swords, pistols, and muskets.’ By evening there was about 7,000 women in a long procession to the royal chateau, dragging behind them the cannons to besiege the palace if the King did not answer them.

On the way the women sang poissarde (fisherwomen) songs, such as one called the Market Women of La Halle

‘If the High Ups still make trouble,

then let the devil confront them,

and since they love gold so much,

let it melt in their mouths,

that is the sincere wish,

of the women who sell fish‘

So the women marched, fourteen miles in pouring rain, to Versailles. When they finally arrived, they were greeted with delighted cries of ‘Vivent Nos Parissiennes!’. They would be joined at Versailles by a former courtesan Theroigne De Mericourt, dramatically attired in a “scarlet riding-habit and… black plume” with a sword by her side and riding a black horse. Always dressed in mens clothes and ready for a fight, Mericourt, like Lacombe, would in later be awarded a civic crown for her role in the uprising of August 10 that established the Insurrectionary Commune – her legend would grow even more when she was imprisoned in Austria for spreading revolutionary propaganda abroad, earning her the title ‘Amazon of Liberty’. For now, she would assist the women by deploying her charms to persuade some of the Royal Bodyguards, alarmed by this filthy army that had descended upon them, into giving up their weapons.

A delegation of fifteen women, drenched and mud splattered, were chosen to present to the National Assembly accusations of price gouging and grain hoarding by the rich, naming, amongst others, the archbishop of Paris. Their sole ally on the National Assembly, one Maximillien Robespierre, confirmed the accusations to the Assembly and demanded an inquiry into grain hoarding. Before the frightened delegates could respond, the thousands of women gathered outside managed to burst into the National Assembly, alleging they had been fired on by Royal bodyguards. The alarmed delegates quickly obtained from the King a signed declaration that all excess grain and flour would be sent immediately to Paris for distribution. He would immediately the decrees abolishing artistocratic privileges and ratify the Rights of Man. However, when the women demanded that the King and the National Assembly return with them to Paris, the King dithered. The women refused to concede this point, and set up camp outside the Royal Palace. The situation escalated late at night on the 5th of October. The head of the National Guard and the ‘hero of the revolution’ Marquis Lafayette finally showed up. He had originally hoped to inspire order by his presence, but his own National Guardsmen let him know that they would support the protesting women, some firing shots above his head, some threatening to hang him if he got in their way. Lafayette therefore had to go to the King alone, and assure him that regardless of what happened with his men, he would die protecting the King.

Then, in the early hours of the morning, some women managed to break into the Royal apartments themselves. Panicked bodyguards fired on them, killing one of them. The crowd, enragedd, rampaged through the palace, killing two of the royal guard. The king found himself and his children barricaded in his rooms while the market women shouted for royal blood. The particularly loathed Marie Antoinette was chased barefoot by a number of these women before finding refuge behind a secret door. The King had no choice but to agree to return to Paris.

On the morning of 6 October, a shaken Lafayette would escort his king to Paris at the heart of a procession of what was now sixty thousand people. Behind them trailed a procession of wagons with food from the King’s personal stores. The National Guard who accompanied the king were joined by the market women who marched with green branches tied to their rifles, the cannons wreathed with laurels, singing that they had brought back the baker, the bakers wife and the bakers son. Amongst this ‘at once joyous and mournful’ procession, the heads of the killed royal bodyguards were brandished on pikes. Royalists and conservatives throughout Europe were outraged. The British Prime Minister Burke decried them as ‘abominations of the furies of hell, in the abused shape of the vilest of women’, to which Mary Wollenstonecraft contemptuously retorted ‘you mean women who gained a livelihood selling vegetables or fish, who never had the advantages of education’.

Aftermath

The women who sold fish and vegetables had indeed accomplished the unthinkable. As the historian Michelet says ‘Men captured the Bastille, but it was women who captured the King’. 5 Octobers heralded a wave of unprecedented political participation by women with a new self-confidence. This was a time when all men, royalist or republican, liberal or Jacobin, believed that women were distinct from men by nature and biology. They were ‘designed’ for domestic rather than public life, more susceptible to emotion and less capable of rational thought. One can imagine the general discomfort when, one month after 5 October, a woman journalist writing for Les Etrennes Nationales hailed the Parisiennes march, saying ‘we suffer more then men, who despite their declarations of rights leave us in a state of inferiority, and, lets be truthful, of slavery.’

Twenty seven cities saw the formation of left wing womens only political clubs in 1789 to 1790. All female companies of the National Guard were formed across France. Women met at the halls below the Jacobin Club, and addressed the radical Cordeliers Club, frequented by men such as Robespierre and Danton. Marat, despised then and now by liberals for his ‘far left views’, was perhaps because of these views one of these women societies’ most enthusiastic advocates, declaring them a gift of providence, to make up for the Jacobins many faults. 1790 saw a motion being raised to extend civil and political rights to women by the Marquis Condorcet in the National Convention, which though doomed from the start

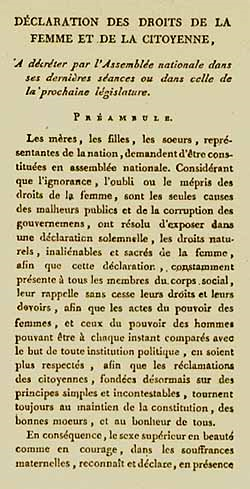

was remarkable in even being proposed. In 1791 the playwright Olympe De Gouges penned her ‘Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen’ in which deliberately referencing the rights of man she declared that ‘women is born free and equal to men in rights’ and “the only limit to the exercise of the natural rights of woman is the perpetual tyranny of man that opposes it”

The apotheosis of the moment came in May 1793 with the formation of the Claire Lacombes and Paulin Leon’s feared society of Revolutionary Republican Women. Madame Petronille Machefer, a street vendor who had now started writing articles under the name La Mere Duschene, wrote ‘let us prove to men that we can equal them in politics. We shall denounce everything that is contrary to the Constitution and above all the rights of women, and we shall teach them there is more spirit and activity in a woman’s little finger than in the whole body of a fat layabout like my very dear husband’

The Society of Revolutionary Republican Women declared their intention that all women from the age eighteen to fifty would form their own seperate army corps, be trained in the use of pistols and swords, and wear a uniform of mens trousers, the bonnet rougue and the revolutionary cockade. They would use their power to safeguard the revolution and strike down ‘the speculators, hoarders and the egoistic merchants’

Even before the conservative reaction of 1794 decisively clamped down on womens activism, more traditional factions of the Jacobin Club became increasingly alarmed at the outspokenness of Lacombe and Leon and their new Society. Women were now asking for the right to be educated, rights of inheritance and right of consent to marriage, which had certainly not been the intentions of the most of the men who began the revolution in 89.

Pauline Leon drafted the Society’s famous petition to the National Convention demanding the right of all women to bear arms just like the men. Leon stated her only aim was to participate equally in the revolution, and ‘the honour of sharing in the men’s..glorious labours and of making tyrants see that women also have blood to shed’. However:

‘If you refuse our just demands..women who have enjoyed the first fruits of liberty, who have conceived the hope of bringing free men into the world, and who have sworn to live free or die; such women will never consent to give birth to slaves, they will sooner die.’

The Society of Revolutionary Women was accused of excessive revolutionary fanaticism, of administering public whippings, beatings and even lynchings of anyone who they deemed counterrevolutionary, and to women who refused to wear the cockade. There was certainly some truth in some of the allegations, but not inconsiderable political motivation behind many of them either. The Society had been instrumental in the expulsion of the moderate Girondin faction from the Jacobin club. It now began siding with the enrages who regularly took positions to the left of the Jacobin club, with much public support. The enrages demanded a maximum price on all essential goods, compulsory loans from the rich, confiscation all the properties of counterrevolutionaries and the expulsion of all nobility from the offices of the state. Leon began calling her onetime ally Robespierre a ‘coward’ for failing to support them. In response, the revolutionary National Convention passed a motion to ban all women’s organisations, declaring that women did not have ‘the physical and moral strength to debate, deliberate or to resist oppression’.

Yet, for the revolutionnaires betrayal, Leon’s claim that having tasted liberty, they would never again submit to slavery proved true. Market women would remain a powerful political force even after the overthrow of the Jacobins, and it would be women who would be instrumental both in the uprising of 1848 and in raising the Paris Commune of 1871. Invariably, in these gatherings one would hear the old poissarde song from 5 October

‘To Versailles, like braggarts,

we dragged our cannons,

although we were only women,

we wanted to show a courage beyond reproach

and men of spirit saw, like them,

That we were not afraid ‘