Amongst young so-called liberals who are my contemporaries, there is a misguided notion that rejection of the ‘classics’ is a form of ‘decolonisation’. Actual figures in the history of decolonisation would consider this foolishness. The liberator of Haiti from the French and organiser of the worlds first and arguably most successful slave revolt, Toussaint Louverture, was a huge admirer of the ancient Romans, irrespective of the fact that he knew as an educated man that they were slavers. It is because Toussaint knews his classics that he could spin revolutionary messages that identified himself and his movement with characters from the ancient world like Lucretia, Hannibal, and of course Spartacus – he bore the eptithet ‘Black Spartacus’ with great pride. It was precisely this which allowed his message to have a global dimension and capture the imaginations of Western Europeans, even in the eighteenth century.

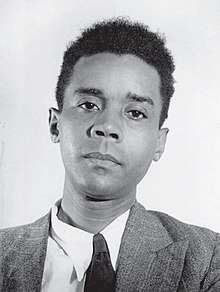

Similarly, the great Trinidadian Marxist CLR James, that passionate chronicler of Western imperialism and campaigner for West Indian independence from Britain, who witnessed the end of colonialism in his lifetime and celeberated the liberation of Ghana along with Kwame Nkrumah and partied with Leon Trotsky, was a huge admirer of the ancient Greeks, and the very British pastimes of cricket and reading William Makepeace Thackerey. People such as these understood the importance of taking knowledge from where to get it and would not simply reject wisdom of ages and the collective inheritance of humanity because a comprehensive review of everything that a certain ancient had said or done revealed unsavoury points of view that don’t sit well with a respected person of the twenty first century – indeed, they valued knowledge because their worlds put up so many barriers to their receiving this knowledge. Same with Marx, the Jacobins and the Leninists – for all their rejection of the traditional organisation of society, they knew their classics and strenghtened their own views with the universal messages that can be distilled from these writings.

Of course, to call ancient Rome and Greece ‘Western’ in the sense we understand now would be somewhat of a misnomer, as the concept of race as we understand it was alien to them. To be a ‘Hellene’ simply meant adopting the language and customs of the ancient Greeks and had no racial dimension- in this, for all their ‘primitive’ views the ancient Greeks were far more advanced than contemporary Europeans.Such distinctions mattered even less in the ancient world – we say the Roman empire ‘fell’ when Rome fell to the Germans, , but in reality Rome hadnt been the capital of Rome for centuries when this happened and had long been consigned to the periphery while the empire itself had relocated its capital to Constantinople in Anatolia, which incidentally, the Romans considered their mythical homeland as descendents of the legendary Aeneas. Rome thus persisted in Turkey for hundreds of years as the ‘Byzantine’ empire, which however always called itself the Roman empire, because that is what it was, since the time of Constantine. Then, this new Rome ‘fell’ to the Turks, but only from a certain perspective. The Ottoman sultan, after the conquest of Constantinople, took the title Sultan-e-Rum, the Sultan of Rome, and it is by this title that he was known throughout the Muslim world and South Asia. The celebrated Persian poet Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi is best known to the world today by his Arabic nickname ‘Rumi’, literally ‘the Roman’.What then does the term east or west mean when applied to Rome, when Rome has been in the middle east for centuries?

There is of course the very real current problem of the exploitation of the Global South by the institutions of global liberalism, based mostly in Europe and the USA, but this is a completely different discussion to the reality of cultural fact of an ‘east’ and ‘west’. European colonialists created these concepts, but they are given a strange second life by these students of postcolonialism. Indeed, a conspiracy theorist might surmise that these postcolonial theories rejecting Western classics, insofar as they are propagated by liberal institutions, encourage the rejection of knowledge by the working classes, the traditional aim of the elites. To refuse to read Voltaire because he was an Islamophobe, Aristotle because he believed in slavery and the inferiority of women, to reject the works of the suffragettes becase so many of their leaders in Britain were anti-semites, is a great act of moronism. Woe betide the society in which subjective lived experience is festishised to the extent that it rejects the need entirely of the writings of the thinkers of old, for that society would have shorn itself from the great tree from which it was born.