“Nations as a natural, God-given way of classifying men, as an inherent..political destiny are a myth; Nationalism, which sometimes takes pre-existing cultures and turns them into nations, sometimes invents them and often obliterates pre-existing cultures; that is the reality” – Ernest Gellner

It has been said that one can be a good patriot, or a good historian, but never both.

Nowhere is this invention of national myth more obvious than in the case of India. The predecessor of the modern Indian state was shaped more by imperial administrative convenience of the British than the contours of history. Her present borders were shaped by the political horse-trading that were the Partition negotiations. Perhaps India was always destined to face crises in identity and legitimacy. In the immediate aftermath of independence in 1947, even the question of naming the newly unshackled country attracted controversy. The two obvious candidates – India, or Hindustan, both had origins which were foreign, unthinkable to the good nationalist.

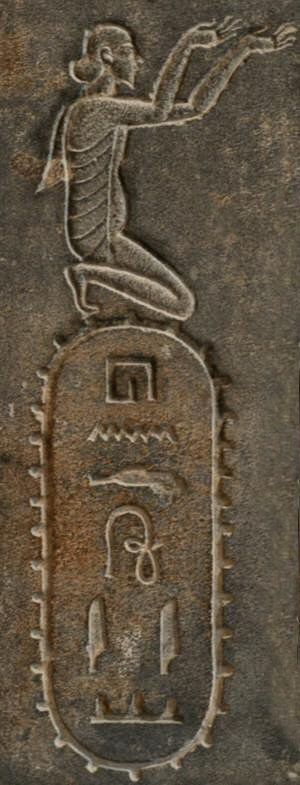

The word India and the word Hindu both have the same etymological origins. The common root word ‘Hindush’ comes not from India at all but from the pre-Islamic Persian Empire. Under the Emperor Cyrus (pronounced ‘Khuroz’) the Persian satraps conquered a province which corresponds to what is today Pakistan and the southern province of Afghanistan. They referred to this province as ‘Hindush’. Where this word comes from is the subject of enduring debate – some say it is a garbling of the word Sindhu, the old Sanskrit word for river – the plains of Northern India were then fed by seven rivers and referred to in Sanskrit texts as ‘sapt Sindhu’ (land of the seven rivers). Regardless of its origin, the Persian appellation ‘Hindu’ for the peoples of that province stuck.

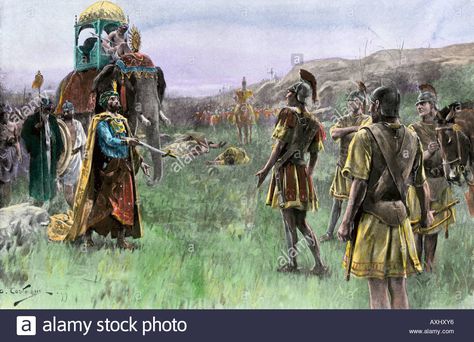

Centuries after the Persian emperor Cyrus, Alexander the Great of Macedon would conquer the Persian empire, utterly overthrowing Cyrus’s descendant Darius III and seizing his vast dominions. After pursuing a rogue general of Darius III to the Persian Hindush’s capital at Taxila, Alexander turned his sights east, and whether through a curiosity to find the edge of the world – which the Greeks thought lay just beyond this easternmost Persian province – or through a desire to be whole known words master, Alexander marched this troops across the Gangetic plain, conquering and subjugating all the way to Bengal. Alexander’s Greeks kept the Persian name for the Hind (noting that the residents of this strange country seemed to worship the Greek God Dionysos) though they dropped the ‘H’ and referred to this lands as ‘India’ or the ‘Indies’. Alexander’s empire was not destined to survive his death and his successor quickly lost control of any lands he had gained in the borders of modern day India, but from the days of Alexander the fabulous ‘Indies’, with its fertile lands, strange beasts and hidden wealth, entered the western imagination.

When the Arab armies first came to the borders of India, they retained that ancient Persian name for the diverse, often completely unrelated pagans of the vast subcontinent and called them ‘Hindus’, and named their land Hindustan, land of the Hindus. Needless to say, the term Hindu was meaningless to the natives of India, as it was always an appellation used by foreigners to describe them. It should be noted that for much of the medieval ages the term Hindustan would only refer to a particular stretch of land from the Punjab to the Gangetic plain, with the kingdoms of the Deccan considered to belong to completely different peoples.

It would only be after centuries of Muslim rule in medieval Hindustan that the people to whom the term applied came to self identify as Hindus. The term ‘Hindu’ is conspicuously absent from any of the sacred texts of Hinduism – the Vedas, the Puranas or the Upanishads, as it is from the great Hindu epics the Ramayana or the Mahabharata. This adds a particularly ironic dimension to the modern Hindu nationalist project and the creation of a ‘pure’ Hindu identity purged of what nationalists view as Islamic accretions.

The foriegn origins of the terms Hindustan and India were well known to the first generation of leaders post Indian independence from the British in 1947. Casting about for alternatives, these ‘founding fathers’ of India would settle on Bharat, which remains the official Hindi name for the country. Bharat as a name certainly has a more a venerable vintage in India – Bharat-varsha (home of the Bharatas) is the setting of the Great Hindu epics- the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The problem historically speaking however is home of the Bharatas was just that- the home of a tribe of Vedic herdsmen called the Bharatas, whose descendants were the heroes of these epics but who in reality were just one of the 34 odd Indo-Aryan tribes named in the Rig Veda. Though they certainly did refer to their land as Bharatvarsh, no one else did, and Bharatvarsh when it was used to describe a functioning real world polity it referred to their small kingdom in the Gangetic plain and nothing else. It is true that in the late classical age the term ‘Bharata’ was still used by some ‘Hindu’ kingdoms, but in the very loose sense to denote the entirety of their known world – from Iran to Srilanka to Tibet. However, Bharata, even in this more expansive sense, had fallen out of usage for millenia until rediscovered ironically by European orientalists and then by the secular Indian nationalists of 1947.

It is scriptural references to this Bharata which have been seized upon devoid of context by the more religious Hindu nationalists to posit the existence of an ancient, forgotten South Asian superstate of whom they are the true inheritors. Faith in scripture can often do away such irrelevances as lack of archaeological record or verifiable historical sources. However, it would not have been lost on the highly educated and more atheistic socialists who were dealing with the national question in 1947 that the subcontinent they sought to rule had never in its long history been ruled as a single entity – not even by the British, for when they left, there were hundreds of independent ‘princely states’ within the present borders of India.

The empire of the fabled Chandragupta Maurya, in the days of Alexander, had come close, which at its height had included modern day Pakistan and Afghanistan and much of the subcontinent (though not modern day Tamil Nadu or Kerala). This would not survive his grandson. A united ‘India’ would not happen again till the Mughals, about twenty centuries later, whose rule once again did not extend to the Southern Indian states. However, it is a mistake to compare these feudal empires to a centralised administrative state in the modern sense – in this, the British Raj was unique. The relation of the lords who administered these vast Indian empires to the central power was essentially one of vassalage – they would pay tithes and tax to the emperor and send armies to him when requested, but in all other matters, they effectively remained absolute sovereigns of their respective domains. When the Mughal empire was at its greatest extent, under Alamgir Aurangzeb, a western observer famously said that the ‘Great Mogul’ was emperor only of the Imperial highways.

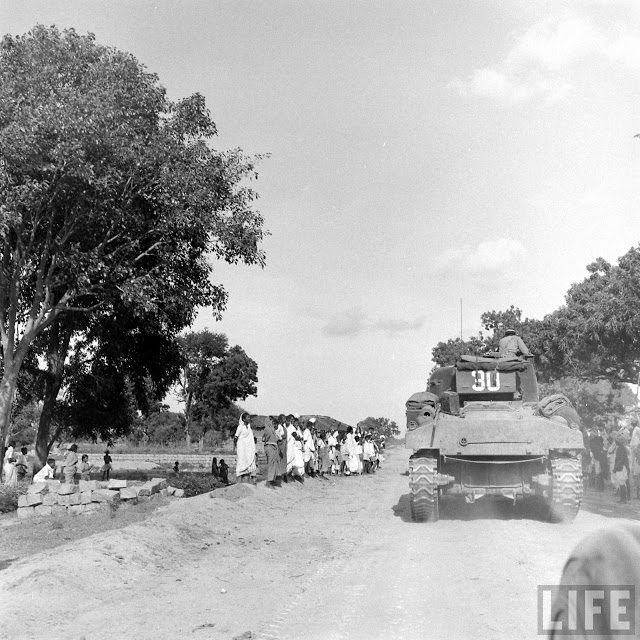

So the issue for the liberators of the country in 1947 was what to do with these aforementioned hundred-odd princely states, which had all been permitted some degree of independence from Delhi by the British. Almost all of these were eventually persuaded to accede to the new state of India. There were some, like Hyderabad, who preferred to maintain their independence. These states required a more vigorous sort of persuasion, the kind accompanied by the barrel of the gun.

When the Nizam of Hyderabad made a stand, an example had to be set. In 1948, 40,000 troops of the newly liberated nation of India marched into the Shia Muslim kingdom to ‘liberate’ its Hindus and annex it, murdering thousands in the process and overthrowing its hereditary Nizams, whom even the British had allowed their sovereignty. The Nizam appealed to the United Nations for intervention, but the international community dragged its feet. The UN had only just been pulled into a dispute involving the similarly independent kingdom of Kashmir and had no appetite to get involved. In the case of that state, a plebiscite promised to the Kashmiri people under the terms of UN ceasefire was studiously ignored by the founding fathers of the new nation. A brutal military occupation lasting six decades would follow.

Having faced these nationalist revolts so soon after their own nationalist revolution against the British, the idea that these diverse peoples were now all in fact members of the single undived nation needed legitimacy. All of a sudden, the notion of an ancient undivided Bharat that existed before the British achieved urgent political currency and was willed into existence in the 20th century.

Under the Hindu right and their ‘Hinudtva’ movement- the movement to create an ethnically and culturally ‘pure’ Hindu state, the undived India project has taken a darker turn. It envisions recreating a Hindu nation that existed not just before the British but the coming of the Islam. Its champions are either ignorant or wilfully ignore the fact that such a nation never existed, and that ‘Hinduism’, ‘Hindustan’ and even ‘Hindi’ – a camp language born from the multicultural melting pot that was the Mughal armies and which is derived as much from Persian and Turki as it is from the local Sanskrit and Prakrit- were all creations of ‘foreign’ rulers. Indigenous Muslim kings and emperors are now referred to as invaders or foreigners, their names slowly removed from the buildings that they built, while minor ‘Hindu’ kings are elevated to proto-Hindu nationalists, an anachronism which would have meant nothing to them

Plato once posited that all socieities are built on ‘a ‘Noble Lie’, a foundational myth that needs to be told and then reinforced for the sake of unity. The American national myth ignores the genocide and the fact of history’s most brutal slavery trade in favour of a romantic myth involving the Delaware crossing and cherry trees. The English national myth ignores the fact that the English did not even get to the British Isles from what is now Germany till the sixth century, hundreds of years after the Romans had come and gone, and that that their success as a nation owes less to liberalism and plucky determination of the Georgians and Victorians than to the vicious system of looting and mass murder that was the British empire.

India is engaged in an ongoing reassessment of its history and Indianness to the active detriment of mostly its Muslim minorities. Contemporary Hinduism and Hindu culture has roots in Persian and Turkish culture every much as the ancient Vedic culture. Nationalist identitarianism and ethnonationalism as it exists in India today has roots in 19th century European political philosophy and would have been alien concepts to the ‘Hindus’ of pre-British India. Yet, with Hindutva on the ascendant and critics of Hindu nationalism regularly branded as anti-nationals and traitors, the telling of these once elemental truths about Indian history has become a revolutionary act.