‘In a rich man’s house, there is no place to spit but his face’

Diogenes of Sinope, 404 BCE to 323 BCE

I

Wild Beasts

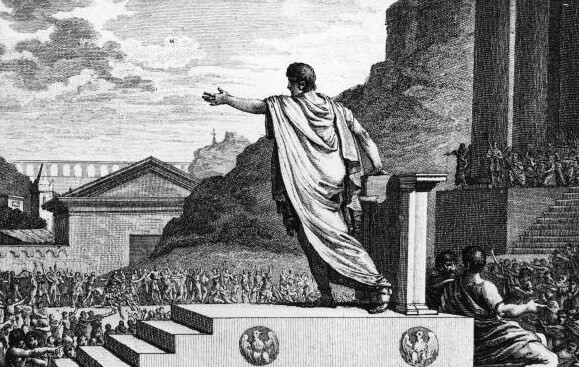

It is the year 134 BCE. A great public assembly is gathered on the Capitoline Hill in the centre of Rome. A thirty year old politician, Tiberius Gracchus, adjusts his trademark black robes, strides up to the large speakers platform in front of the temple of Jupiter and addresses the immense throng. It takes him no time to silence the crowd, as many of them have travelled for weeks from distant parts of Italy just to hear him speak. He does not know it, but he will go onto deliver a speech which would seal both his fate, and shake the very foundations of the Roman republic.

In his calm, deliberate manner, Tiberius delivered a blistering attack on the Senate, the main legislative body of the Republic and the seat of all power in Rome. He knew his subject well – he, Tiberius Gracchus, was after all one of the two people elected as the ordinary citizens representatives to the Senate – a ‘tribune’ of the non noble class known as the plebeians,or the ‘plebs’. Tiberius speaks of the age of heroes five centuries ago, when their ancestors, alone amongst all the peoples of the world, had done away with kings forever, and had taken a sacred vow that in Rome, only ‘the people’ would rule. Rome had gone in that time from a small village to masters not only of Italy, but of unheard of kingdoms in Africa and Asia. All of that wealth and land had not however gone to the people but into the personal fortunes of the immensely wealthy noble families who made up the Senate

These Senators had not just appropriated for their private fortunes all the wealth from Rome’s endless foreign wars, paid for with plebeian blood. They had used the newly acquired money to buy up all the farming land in Italy, dispossessing en masse the citizen-farmers that had always been the backbone of the Roman republic. The situation had been summed up well by the recently deceased senator Cato the Elder: “Thieves of private property pass their lives in chains; thieves of public property in riches and luxury”

It was in this context that Tiberius Gracchus spoke the words by which he would be immortalised

‘The wild beasts that roam over Italy have every one of them a cave or lair to lurk in…While the men who fight and die for Italy enjoy the common air and light and nothing else. Houseless and homeless they wander about with their wives and children..they fight and die to support others in wealth and luxury..though as Romans they are styled as Masters of the World, they have not a single clod of earth to call their own‘.

The conflict being described by Tiberius would dominate the next one hundred years of the Roman Republic. It would end with the fall of the Republic and the birth of the Empire, where decisions would no longer be made by an elected Senate but by one man, the Emperor. Under its Emperors Rome would grow more powerful than ever and endure for centuries. However it came at a great cost -for the like of the Republic would not be seen again in Western Europe until the great democratic revolutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, nearly two millenia later. The French, British and American anti-monarchists would explicitly model their new ‘republics’ on the lost republic of ancient Rome. Even the word republic was taken from this period (the Latin res publica, ‘our public thing’). Insomuch as the French, British and the Americans would then go onto impose their models of governance on the whole world, the story of the collapse of the original republic and the populism that bought about its end seems timely, even with all the caveats about comparing different historical eras.

After whipping the crowd up into a frenzy with his ‘Wild beasts of Italy’ speech, Tiberius Gracchus delivered his coup de grace. He introduced a bill called the Lex Agraria. The bill stipulated that henceforth, there would be an upper limit on the amount of land a single man could own – anything in excess of it would be become public land and be redistributed to landless citizens. Crucially the bill also said that any land which Rome acquired in her overseas adventures would not go up for sale to the highest bidder but be redistributed to the public as farming lands .

Tiberius told the crowd gathered on the Capitoline Hill how he had of course initially pursued his bill through the normal channels, and had introduced it in the Senate. He told them how the men of the Senate had reacted as rich men have always done when confronted with wealth redistribution. He, the tribune of the plebs, their sacred representative, had been laughed out of the chamber. However, Tiberius declared triumphantly, they did not need the Senate. According to laws unused for centuries a people’s assembly had the power to pass laws without the agreement of those corrupt old men – they could, right now, vote on this bill, and sieze control of their own destinies. To the roars of the audience, he proposed to put the vote to them, the ordinary men of Rome.

This was all too much for one man. Marcus Octavius, the other tribune of the plebeians and Gracchus’s co-leader of the assembly. was every bit a creature of the Senate. He stood up and imperiously shouted ‘veto’ (Latin for ‘I forbid’). It was all Tiberius could do to keep the furious mob from tearing Octavius apart, until his bodyguard were able to push their way through the crowd and shepherd Octavius to safety.

The Senate was horrified to hear of these developments. The once powerful plebeian assemblies had long been subordinatedto them, and by centuries of custom prevented from introducing any bill without the Senates’ prior approval. They commanded Octavius to ensure the bill never became law, and Octavius vetoed every vote on land redistribution that followed in the peoples’ assemblies.

Tiberius finally put it to the assembly that if Octavius would not let them vote on the redistribution bill, then they could vote to remove Octavius from his role as their tribune. This was at the time, unthinkable – the power sharing arrangement between Tiberius and Octavius was one that mirrored at every level in the Roman Republic and was fundamental to it. The way the Romans had protected their democratic traditions in an age of universal autocracy was an almost fanatical adherence to the principle that no single person was allowed to hold too much power. The head of the Republic was the Consul, but even this office was shared by two people, who alternated supreme power every month. This small measure of power was further diluted by laws stating that Consuls, like Tribunes and indeed anyone elected to any senior office in Rome, could only serve in their post for a single year, after which fresh elections were required to be held. The person who had just served in the post could not run for re-election in the same post for at least ten years. These traditions had been preserved without exception for the five hundred years since the overthrow of the last king of Rome. So great was the aversion to kings that it was legal for any citizen to kill, at any time and without reprisal, any other citizen they could prove had sought kingly power.

The people were pissed, however, and the vote to remove Octavius as co-tribune was unanimous. Now sole tribune of the plebs, Tiberius pushed the vote on land redistribution and the Lex Agraria became law. It was Tiberius Gracchus’s finest hour, but he succeeded also in completely alienating the Senate. Even the few reformist backers he had in the Senate abandoned him for his transgression of the Republic’s sacred laws, including his own uncle, the famed Scipio Amelianus, conqueror of Carthage. The Senate still controlled the purse-strings of the government and dominated the judiciary, and went out of their way to make sure that Gracchus’s redistribution laws were not enforceable in practice. Their strategy was to wait out Tiberius’s year as tribune, and once he stepped down, to replace him with a more traditionally pliant tribune of the plebs who would allow this whole thing to die. Tiberius Gracchus however would not be outmanoeuvred. Surrounded by thousands of armed supporters from the lower rungs of society, he made a shocking announcement. He would run for an unheard of second term. The announcement was greeted with jubilation by the plebeian assemblies.

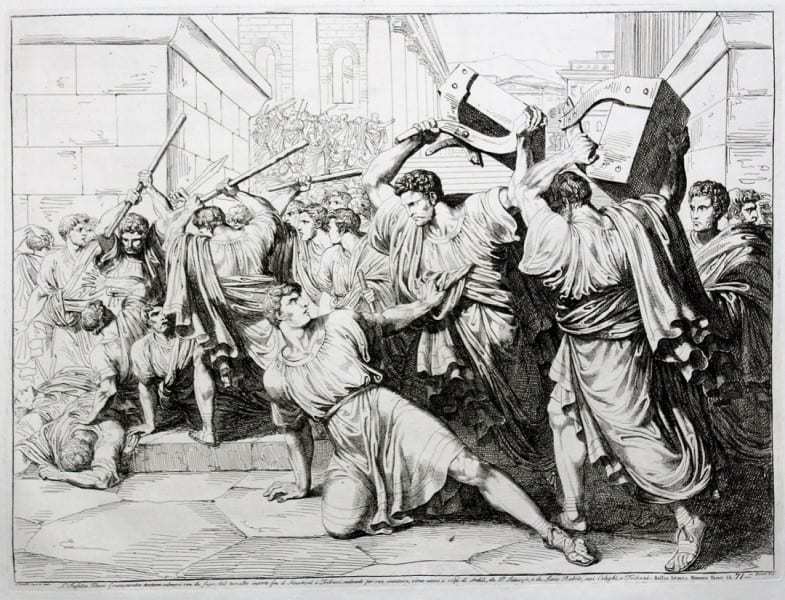

This was too much for the Senate. The Chief High Priest, the Pontifex Maximus of Rome, a senator named Nasica, accused Tiberius of conspiring to make himself king. Nasica rose in the Senate on the day of the controversial election and declared ‘Let those who would save our country follow me’.

Nasica then led a mob of like minded senators to the Capitoline Hill where Tiberius Gracchus was giving a speech in front of his supporters. At Nasica’s command, they descended on the Gracchans and began beating them mercilessly. Finally, they found Tiberius and clubbed him to death on the steps of the Temple of Jupiter in broad daylight, even though as tribune, his body was supposedly sacrosanct. At the end of the day about three hundred people lay dead. All of the bodies, including Tiberius’s, were unceremoniously dumped in the Tiber.

The Senate then set up an extraordinary tribunal to investigate those responsible for the massacre, but the hundreds sentenced by the tribunal were to a to a man low class plebs who had supported Tiberius Gracchus – not a single senator was prosecuted. To make matters worse, Nasica, who had arranged the sacrilegious murder of the tribune of the plebs, openly walked around in his priestly robes, a free man.

The Senate did not care. They were complacent in the knowledge that they had crushed Tiberius’s rebellion. They did not know that a storm was coming – a gathering black cloud of vengeance in the form of Tiberius’s younger brother, Gaius Gracchus.

II

Gaius Gracchus

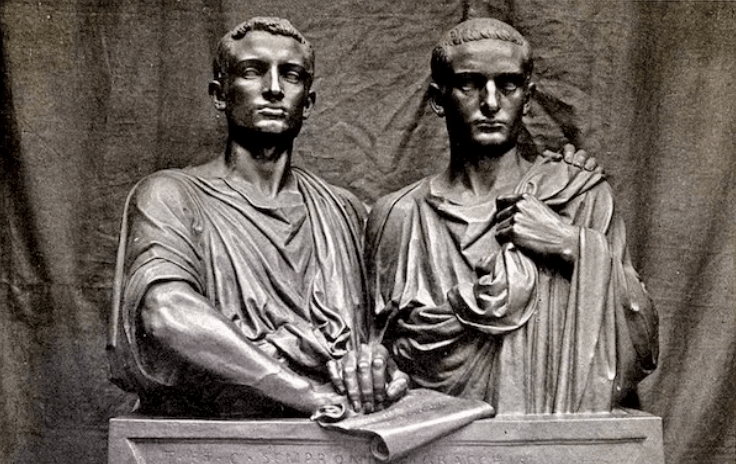

While Tiberius had been politicking, the young Gaius had been away doing military service in Spain. Returning to Rome the year after his brother’s very public murder, Gaius found himself at the age of twenty two the inheritor of a whole movement. Plutarch says that Gaius was in every way the opposite of his brother. Where Tiberius was calm and dignified, and austere in his personal life, Gaius was passionate and hot headed, with ‘a love for ostentation’. Yet, in oratory, he found himself every bit his brother’s match, inventing a much imitated theatrical form in which he would pace the rostra energetically, gesturing and pulling his toga off his chest as he spoke. The myth of his brother proved a potent source of inspiration for his rabble rousing speeches against the Senate:

“Before your eyes, these men beat Tiberius to death with clubs, and dragged his body from the Capitol though the midst of the city to be dumped into the Tiber. ..Those of his friends who were caught were put to death without trial”

Along with land redistribution, Gauis added two key new demands to Tiberius’s radical reforms. The first was extension of Roman citizenship to all Italians. Rome was by now the supreme power in Italy, but her jealously guarded democratic traditions, which included not just the right to vote but a whole package of basic civil liberties, were restricted only to a small group of residents of the city of Rome. The Senate watched helplessly as once loyal Italian allied cities across the peninsula exploded with violent demonstrations for equal rights. This also gave Gaius an immense base of popular support which dwarfed even that of Tiberius. The second new demand was the creation of a grain dole for poor citizens, gaining him support among non-voting urban poor. Together with his brothers supporters, this was all the coalition he needed to win the fiercely contested elections for the new tribune of the plebs, despite open hostility from the Senate.

The plebeian assemblies under Gaius became a hotbed of radical politics- and even some on the Senate began to come around. The supporters of these new policies became known as the ‘populares‘ – literally, the populists – while the traditionalists in the Senate came to be known as the ‘optimates’ – the ‘best’, or ‘the elites’.

The influence of the populares under Gaius was such that one of their own was elected Consul, the highest office of the Republic – a family friend of Gaius named Flaccus. Through Flaccus, Gaius was able to revenge himself on his brothers’ killers. The High Priest Nasica was finally convicted of Tiberius’s murder and exiled from Rome, never to return. Octavius, who had done so much to block Tiberius’s reforms, was barred from ever standing from political office. High ranking conservative Senators suddenly found themselves the subject of corruption and bribery investigations.

Secure in his untouchability, Gaius Gracchus announced that he would now do the very thing that had killed this brother. Thumbing his nose at the laws of the Republic, he campaigned for and effortlessly won the forbidden second term as tribune of the plebs. Tiberius’s long-neglected land redistribution commission now found itself in funds, and was able to ensure that the lands acquired from the recent conquest of Carthage were allocated to pleb farmers.

III

The Republic Strikes Back

When Gaius travelled away from Rome to personally supervise the commissions work, however, the Senate struck back. They ensured the election of a new Consul called Lucius Opimius, a man with impeccable aristocratic credentials and a streak of bloodthirstiness. Before becoming Consul, Opimius decided to end the Italian citzenship demonstrations once and for all by making an example of an Italian city that had risen in revolt. He oversaw the total destruction of the town of Fregellae, near the modern town of Ceprano in central Italy, and ordered a general massacre of its rioting citizens. Fregellae had been a loyal Roman ally for hundreds of years and her sons had distinguished themselves in the wars against Carthage, and even anti-Italian conservatives balked at the brutal action.

Nonetheless, Opimius became Consul, and did everything he could to dismantle Gaius’ legislation. He declared Gaius a fomenter of rebellion and enemy of the state. Gaius announced in response that he would now run for a manifestly illegal third term, to ensure his important work in service of ‘the people’ could be carried out. In the huge demonstrations that followed, a scuffle broke out between his supporters and Opimius’s, in which one of Opimius’s men was killed. This was all the pretext Opimius needed. He commanded every nobleman in Rome to give him two armed men each. With this army, he marched on Gaius’s home.

Throughout his life, Gauis spoke of having a recurring dream where the ghost of his brother appeared to him, clad in his black robes. Even as his political star rose and he went from success to success, the ghostly figure would tell him, or so he complained, ‘However much you may try to defer your fate, you must die the same death that I did”.

It may have been propaganda concocted to further his political career. Still, that fateful day, as Opimius’s army marched on him, Gaius faced the prospect of this bleak prophecy being realised. Flaccus rushed to defend him, confident that no one would dare lay a hand on a former Consul of the Republic. Opiumius’s men beheaded Flaccus in the street without a second thought, before setting upon Gaius’ followers. Gaius was the only man who escaped the resulting massacre, but he would commit suicide that same day, as Opimius’s men closed in on him. In the days that followed, the Senate ordered the execution of thousands of prominent Gracchan supporters and their families.

The death of Gaius Gracchus

IV

Aftermath

The Gracchi brothers were dead, but the populares were far from finished as a powerful political movement, and they hounded the Republic to its last days. Their cause would now be taken up by Rome’s most distinguished general and war hero, a man named Gaius Marius. His career, the story of a soldier of ‘rustic birth, rough and uncouth’ rising to the Consulship of Rome, opposed at each stage by conservative Senators, could be the subject of another blog this size. Suffice to say, with the taboo against consecutive terms now broken, Marius served a positively sacrilegious seven terms as Consul. This gave him the time to enact reforms so far reaching he earned the title ‘the third founder of Rome’. The Senate would have to respond with their own general, a man named Lucius Cornelia Sulla Felix. The fight between Optimates and the Populares, fought in Tiberius’s days by rival mobs on the Capitoline Hill, would now be fought between rival armies as Rome descended into civil war.

Sulla, champion of the Senate, was ultimately triumphant by default as Marius succumbed to old age. Sulla then became the first man to march on Rome with an army and seize power by force. Sulla’s resulting purges of the peoples assemblies were even bloodier than Opimius’s. Every day, proscribed lists of populare supporters would be posted on the Forum, and nine thousand populares were summarily executed as Sulla’s death squads roamed the city. Sulla decreed that the pleb assemblies could no longer pass legislation of their own accord, nor veto legislation from the Senate. When he finally relinquished power, he did so in the knowledge he finally had restored the Senate as the supreme power of Rome.

Sulla’s restoration would in fact not even last a generation. One young boy would escape Sulla’s purges, a teenaged nephew of Marius. Marked for death on Sulla’s proscribed lists, he would spend his youth on the run. With his return to Rome as a young man, he would take up the populare cause begun by the Gracchi brothers, with the familiar battle cries of land redistribution, the grain dole, and an expansion of citizens rights. Sulla was prescient when marking the child for death, for he would certainly go onto become the Senates most formidable enemy.

His name was Julius Caesar, and the rest, of course, is history,

Caesar would cross the Rubicon and crush the Senate. Eager to prevent another Opimius or Sulla ever coming for them again, Caesar’s populare partisans would cheerfully appoint their own champion Caesar Dictator for Life. When a handful of Senators assassinated the Dictator on the Ides of March, they would finally realise how disenchanted people had become with the Republic. Instead of cheering the Senators as liberators, the poor rioted, burned down their estates, and chased them out of Rome. Julius’s successor Augustus Caesar would become the first emperor and would rule on his own for forty years. Though Augustus and his successors were careful to maintain the illusion of republicanism – the official title of the emperors was not ‘Imperator’ (’emperor’) at all but ‘Princeps’, “First Citizen” – Rome would henceforth be a monarchy in all but name. The legacy of the Emperors is complicated – on the one hand, they achieved much of the populare programme. Every citizen of Rome would from the time of Augustus be entitled to a free daily bread ration. They would instute the public work projects and infrastructure for which Rome became famous. The extension of rights continued until the Emperor Caracalla granted every free man in the Roman Empire equal citizenship in 212 AD. On the other hand, the people would never again be able to choose their leaders, vote on their own laws or criticise the government without fear of reprisal. The lost liberty of the Ancestors would become a cherished dream.

The tragedy of the Republic is that it could have been saved, had a few elites prioritised much needed reform over their own selfish interests. Instead, they took the Republic for granted, assured that her centuries old democratic traditions would continue to endure forever, no matter what they did. Even the ‘last defender of the Republic’, the lawyer Cicero, put to death for speaking out against the Dictatorship, had early in his life predicted that the demise of the Republic would come out of the excessive inequality and naked greed that defined its last days:

‘We are silent when we see all the money of all nations have come into the hands of a few men; which we seem to tolerate and to permit with the more equanimity , because none of these robbers conceals what they are doing’

– Cicero

This piece does a fantastic job of combining solid research with a simple, engaging writing style. The use of little-known facts keeps the reader curious and eager to learn more. It’s refreshing to see complex information presented in a way that’s easy to understand without feeling watered down. The surprising details sprinkled throughout not only inform but also entertain—making it a memorable read..