A strange and star crossed tale of India’s second Mughal emperor

Background

I recently visited the tomb of Mughal Emperor Humayun in Old Delhi. It is built to be close to the tomb of the great Sufi Mystic Nizammuddin Auliya, which still attracts pilgrims as it did back in Humayun’s day, five hundred years ago. Humayun’s serene mausoleum bears the unmistakable template for the great buildings of the Mughals that will one day be perfected in the Taj Mahal. The trademark great marble dome and flutelike minarets are all there, and stand guard over not just Humayun but a veritable inhabitation of spirits. 108 members of the imperial family are buried here. It is here too that the Mughal empire itself died a symbolic death, when, in the sack of Delhi by the British in 1857, the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar took refuge here amongst his dead forbears. He was eventually captured by William Hodgson and sent packing into exile in Rangoon, where he is buried, while his sons were shot by the British, the last lights of an empire that had once been the richest in the world. The restless dead’s spectral aura hangs over the mausoleums gardens, which are surprisingly clean and well preserved, though its many canals and fountains have long stood dry.

Old English travellers reports say said that visitors could once see Humayun’s sword, turban and slippers over his grave, that the massive geometric interiors were once richly furnished with carpets and white sheets of silk and beautifully decorated copies of the Quran. Yet, even without these, there is something about these plain symmetries of the white chambers that soothes the onlookers mind. The mournful, haunted place inspired me to do a short instagram post about this much maligned and overlooked Mughal emperor, and in turn this biography about the emperor’s life.

Humayun was the second of the dynasty somewhat incorrectly known as the ‘Mughals’ – from the Persian word for Mongol. Although they did have Mongol ancestry – Humayun’s grandmother was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan – they identified themselves as Chagatai Turks and considered their progenitor the fearsome thirteenth century Turkic warlord Timur (Tamerlane in the West). The Mughals ruled at their height large swathes of what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and even lands which are now in Iran, and the empire persisted in Delhi until its conquest by the British in the late nineteenth century.

Poor Humayun is rarely the first name which springs to mind when people talk about the Mughals – he has had to spend his afterlife in the shadow of his father, Babur, the first Mughal, who established the dynasty, and his son, Akbar, the greatest of all the Mughal emperors, who transformed what was essentially a thin strip of land from Kabul to Delhi into a subcontinent spanning empire, and whose unprecedented religious tolerance and patronage of Hindu art and music set the basis for a uniquely syncretic culture that still forms the backbone of North Indian culture. In contrast to these empire builders,Humauyun is best remembered as the man who almost lost the Mughal empire – an opium addicted dilettante, who preferred his hobbies of astrology, star gazing and wine parties to the business of ruling, And of course, Humayun also now faces the same posthumous demonisation that all Islamic rulers face in contemporary India, with the rise of the Hindu Right and their narrative of ‘thousand years of oppression’ under Islam – a fate which not even the once universally admired Akbar has escaped. A cruel destiny indeed for Humayun, who was famed for his gentleness and generosity in his lifetime. Even amongst his enemies he was called ‘insaan-e-kaamil’ – the perfect gentleman.

The rise of the House of Timur

In addition to the number of unofficial biographies and court diaries that survive from his time, Humayun benefits from two biographies written by people who personally knew him and witnessed many of the incidents they describe – the Humayun Namah, written by his indomitable niece Gulbadan Begum, and the Tezkereh Al Vakiat, the memoirs of his personal valet and water bearer Jauhar.. One incident from Jauhar’s memoirs perfectly captures both Humayun’s personality and his unsuitability for life in the brutal world that was sixteenth century India.. During a victory over the Sultan of Gujarat early on in his reign, the Mughal armies captured a leading enemy general. As the Mughals had been unsuccessfully trying to locate the Gujarati sultans treasury to pay their troops, several of Humayun’s generals counselled him to torture the general to get him to give up the location of the treasure. Humayun refused, saying “If an object can be attained by gentleness, why have recourse to harsh measures? Give ye orders instead that a banquet be prepared, and ply him well with wine, and then ask him the question”.

Humayun was born in 1508 in Kabul, to which his father Babur had been effectively exiled from his ancestral home of Ferghana in modern Uzbekistan. Babur had inherited Kabul from a distant uncle after a youth spent, in his own words, wandering “from mountain to mountain, homeless and houseless, without country or abiding-place” The blood feud between Babur and the man who had ousted him from his throne when he was eleven years old- the Uzbek Shiyabani Khan- was the stuff of legend,. Shiyabani Khan’s men had kidnapped Babur’s beloved sister Khanzada Begum at the same time as he had made him a refugee, and forcibly inducted her into his harem. Babur had spent a lifetime unsuccessfully fighting to get his home and his sister back. Following a number of defeats, he was reduced to hiding from the Uzbek in Kabul,obsessively guarding its mountain passes. Determined to build a legacy for his son after a youth spent in poverty, Babur spent the next ten years setting up a base for himself in Kabul, in those days a rich trading post on the Silk Road, and styling himself Badshah (King). He invited all of the nobility of the house of Timur to seek refuge there from the relentless persecutions of Shiyabani Khan. So in Kabul Babur patiently began training an international army of exiles, mercenaries and fortune seekers loyal to him, enriching himself not just from trade on the Silk Road but from raids into surrounding countries in the style of his Mongol cousins. At the same time, he indulged in his passions for literature and gardening, inviting poets and intellectuals from Persia and Central Asia to Kabul, founding schools, building public gardens, writing his famous diary and even finding time to a develop a style of calligraphy of his own called Baburi. He ensured that Humayun had an education becoming of a young prince of the blood, and from his father Humayun inherited a lifelong love of books.

.

Babur began to fear however that his son had inherited little else from him and remarked often about the worrying lack of urgency in the young prince. Humayun’s first test as a teenager was being awarded the governership of Badakshan, and Babur complains about his son’s tardiness. On one occasion, his teenage son had even written to him saying that he had no interest in governing, and wished to retire and become a wandering holy man, and Babur wrote to him, chiding “As for the retirement you mention in your letters…retirement is a fault for sovereignty…rule does not allow retirement”. A keen poet himself, Babur even found cause to disparage his sons writing, informing him his prose took too long to come to the point..

Also concerning was Humayun’s growing reputation as somewhat of a libertine. “In battle he was steady and brave, in conversation ingenious and lively and at the social board, full of wit” wrote a courtier, Mirza Haidar, about the prince, ‘He was kind hearted and generous.. a dignified and magnificent prince who observed much state, but in consequence of having dissolute and sensual men in his service..he contracted some bad habits, such as the excessive consumption of opium..”

By the 1520s, however, there were other things to occupy Babur’s mind. Things were finally looking up for him. Shiyabani Khan had finally overreached and attempted to invade Persia, and ended up getting himself killed by the Persian Shah Ismail. His freed sister Khanzada Begum made her way back to him in a scene of much rejoicing. The Persian king also for good measure also had the skull of Babur’s old Uzbek nemesis hollowed out, plated in gold and made into a drinking cup.

To Babur’s south, the kingdom of Delhi was in turmoil. Then ruled by an Afghani dynasty called the Lodi dynasty, the capable old monarch Sikander Lodi had recently died and his successor, Ibrahim Lodi, was a potent combination of lack of ability with a tendency towards tyrannical absolutism. Ibrahim’s governors were soon in open revolt and finally sensing an opportunity to gain a kingdom to match his self appointed title, after waiting for the auspicious moment when “the sun rose in the sign of the Archer” Babur led his warband into India, toward an all or nothing confrontation with the Lodis at Panipat, near Delhi, in 1526.

The embattled Lodi king met Babur at Panipat with an army four times his size, but Babur had a secret weapon – gunpowder, at the time unknown in the battlefields of India. The win by Babur changed not only the history of India but the entire Islamic world – in which the Mughals would become a rival centre of power to the Persians and the Ottomans. Yet it almost didn’t happen, Babur writes, because Humayun, who was meant to lead the vanguard of the Mughal armies, turned up to the battle three days late.

On balance however, Humayun seems to have acquitted himself well at Panipat,capturing a hundred prisoners and eight elephants. He also fought alongside his father the following year during the great battle of Khanua against a confederacy of Rajput kings led by the one-eyed, one-legged veteran of a hundred battles, Rana Sangha of Mewar.

Eyeing Humayun’s fortunes were his three younger half-brothers, Baburs sons by other consorts – the fierce Kamran, wily Askari and the young but impressionable Hindal, who were all as ambitious as Humayun was languorous. Kamran in particular was a formidable warrior, and chafed at being left in charge of Kandahar in what is today northern Afghanistan while his brother went off to win glory. Then in 1530, Babur fell gravely ill it was Humayun who was summoned to him rather than these more warlike brothers – for all their differences, Humayun remained his favourite son. After extracting a promise from Humayun not to spill the blood of his brothers, no matter how much they may deserve it, Babur died.

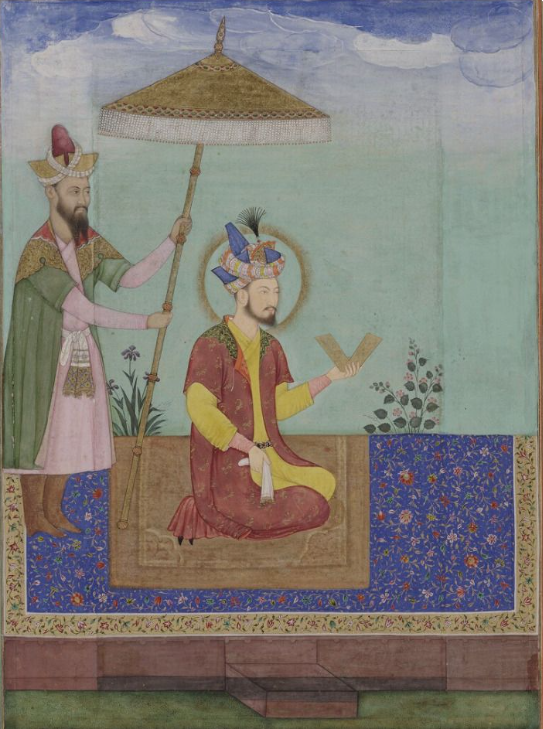

The Star King

So it was that Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun, unlikely descendant of Genghis Khan and Timur, became Badshah of Hindustan. In the tradition of horse lords of the Steppe, Babur’s empire was divided between his sons, with Humayun getting the throne of Delhi and the second eldest Kamran the throne of Kabul. Askari and Hindal got subordinate provinces to each of them. .

Immediately, Kamran came south and seized some of Humayun’s lands in the Punjab for his own. For any other king, this would have been war, but Humayun not only wrote to his brother telling him he could keep the lands, but also offered him some more. A rebellion by Askari during the early 1530s was also similarly forgiven.

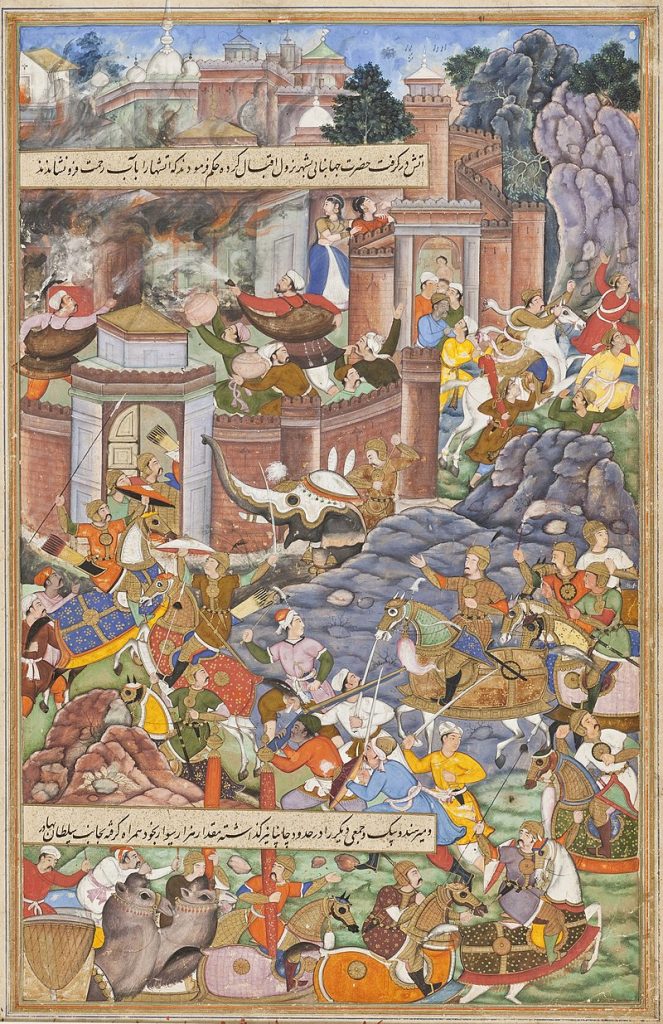

In fairness to Humayun, in contrast to his indulgence of his brothers, he pursued a robust campaign in those early years against various cousins and uncles with designs on his throne, and dealt swiftly with the threat of the still numerous Afghani supporters of the old Lodi Kings. Chief amongst this latter threat was the sultan of Gujarat, Bahadur Shah,the very same whose general Humayun had refused to torture, and around whom these Lodi loyalists began to gather. Humayun pounded down Bahadur Shah’s fortress of Mandu with two massive cannons called ‘Laila’ and ‘Majnu’. He siezed another of fortresses in Champaner in a daring action where he scaled a sheer rock face together with three hundred men using handheld spikes. After a year in the saddle, Humayun succeeded in adding almost the whole of Gujarat to the young Mughal empire. Bahadur Shah himself however was allowed to escape, though Humayun chased him to the gulf of Cambay, where he became the first person of his family to gaze upon the sea.

However, after these initial victories, Humayun ‘unfurled the carpet of pleasure’ and gave himself over to opium and wine parties and his arcane intellectual pursuits. It was during this time that Humayun’s lifelong obsession with astrology really overtook him – he constantly gazed at the cold and distant stars through his astrolabe and pored over astrology charts for signs on how to rule his kingdom,. Coming under the influence of two Shattari Sufis – highly respected Hindustani saints – Shaikh Gawth and Shaikh Phul- he took to wearing different coloured clothes on each day according to the ruling planet. He even alllowed the planets to dictate government business – so on Tuesdays, for example, he would wear the red vestment of Mars, and only conduct business of war; Sundays were days dedicated to the sun that “regulated” sovereignty and the day to wear yellow and deal with matters of state; Monday was a day of “joy” and a day to wear green; and so on. He devised a system to reorganise his government departments according to the classical elements – fire for the armed forces, air for the kitchens and the stables, water for the canals and the wine cellars, and earth for agriculture and building projects, with staff members of each department given astrologically appropriate clothing. An oft commented on astrological game designed by Humayun involved a so-called the ‘carpet of mirth’, embroidered with the constellations and where his courtiers were made to stand, sit down, or recline according to rolls of a die and various alignments of the planets.

Historians from Humayun’s time till now have delighted in recounting these incidents as those of a royal opium addict given free reign to indulge in his eccentricites, however some historians have suggested that there was some method to this apparent madness. The stars were serious business in the mediaeval world, and as much as bloodlines, or conquest, the mandate of heaven could be used to legitimise the sovereignty of young dynasties, like the Mughals were then. Humayun’s ancestor Timur had no ancient bloodline to speak of, but he had holy men declare him ‘Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction’ (Sahib Qiran), i.e. a person born under a rare alignment of Jupiter and Saturn, which marked one as a saviour of mankind and a favoured child of the heavens. These traditions harked back to the pre-Islamic pagan roots of Central Asian culture and provided an ancient alternative basis for legitimacy. Humayun would go to great lengths to ensure his eldest son was born under such a conjunction of stars, timing his conception and his birth to ensure he was born under the Auspicious Conjunction.

The association with the Sheikhs Gawth and Shiekh Phul was also in a sense political, in that it represented a break by Humayun from the Nakshabandhi Sufis of Central Asia who his family had traditionally patronised and a reorientation towards an indigenous source of legitimacy. This has been described by the historian Ira Mukhoty as “the first use by the Mughals of Hindustani intermediaries familiar with both Persian and local forms of worship” and a knowledge of “indigenous cosmological forces” Sheikh Phul in particular was believed to be able control the planets with his incantations and claimed, in the words of Mukhoty “the not inconsiderable miracle of being escorted by the angel Gabruel himself through the seven heavens to witness the glory of God”. Humayuns obsession with the mystical,in Mukhoty’s view, was an attempt to build a powerful sacred symbolism for his successors to draw on.

The lines between astrology and astronomy of course were thin those days, and so as byproduct of this obsession Humayun became a patron of mathematics and the nascent scientific movement – in fact, Humayun was quite an accomplished mathematician himself. He also was a keen inventor, designing a floating palace and a transportable bridge. A double barge which he designed cruised down the Yamuna. He also oversaw the construction of a new citadel in Delhi called ‘Dinapanah’. The citadel was later razed but its walls are still visible in Old Delhi today as part of the ‘Puranah Kila’.

The Tiger Lord comes

Humayun’s enemies, however, used this time in gather their power. Humayun chose to ignore rumours that Bahadur Shah had returned, in an alliance with the Portugese and assisted by four thousand Ethiopian mercenaries, and was slowly taking back Gujarat. Worse still in Bihar, an Afghani of the Sur Tribe called Sher Khan (literally, Tiger Lord) was being hailed as a great new war leader of the ever tumultuous Afghanis. Humayun ignored the pleas of all of his vassals in the region about the danger this man posed to him, until the Tiger Lord raised an army and conquered the wealthy region of Bengal, installing himself in its capital Gaur and sending its king to seek asylum in Humayun’s court. In 1537, Humayun was finally roused to put together an army and make a characteristically unhurried journey to Bengal.

In contrast to Humayun, Sher Khan was a man of humble origins, son of a lowly horse trader, who rose up through the ranks through sheer ability. One Mughal ambassador to his camp was surprised to see the Khan stripped naked to the waist and helping his labourers dig a trench with his own hands. This unbecoming man, who addressed the ambassador with a disarming lack of formality, would run rings around Humayun in Bengal.

Humayun’s much larger army originally had some victories and even captured Gaur. However, instead of chasing after Sher Khan and his son, Humayun decided to spend months restoring Gaurs damaged buildings and palaces, and, in the words of Jauhar “unaccountably shut himself in his harem for months”. While Humayun holidayed in his new province, Sher Khan gathered his strength, and went around the Mughal armies back, cutting them off from any retreat. At this crucial time, Humayun’s always duplicitous brothers struck again. Hindal, who was supposed to be guarding Humayun’s rear in case this very thing happened, went back to Agra and declared himself emperor, hoping that Humayun would be killed. Kamran came down from Kabul, ostensibly to punish Hindal, but with his army also did not move to help Humayun either, opting to see how the situation played out. Askari meanwhile did offer to help, but only if his brother paid him in elephants, pretty concubines, eunuchs and gold. .

After a long campaign of guerilla warfare where he whittled down Humayun’s army, Sher Khan finally lured Humayun into battle at Chausa near Varanasi and smashed his army to bits. Humayun barely escaped with his life, jumping into the Ganges and swimming to safety on an air filled water skin. He made his way back to Agra, where, incredibly and much to exasperation of all his well-wishers, he forgave his brothers and let Kamran return home to Kabul. Sher Khan, meanwhile, quickly moved to capture first Agra and then Delhi, again leaving Humayun to flee for his life. Kamran refused to give him asylum in Kabul, knowing that he would be bound to hand the city over to his brother.. It was at this point that Sher Khan revealed that Kamran had been writing to him the whole time to seek an alliance, but that he had refused to enter an alliance with someone who would so willingly betray their own family. Humayun’s supporters confronted him with this, and when they asked why he did not have Kamran killed when he had the chance, Humayun responded “No, never, for the vanities of this perishable world, will I imbrue my hands in the blood of a brother”

So it was that Sher Khan declared himself new emperor of Hindustan ‘Sher Shah Suri’. He and his son would rule for 15 years, while Humayun would spend this entire time a refugee,a king without a kingdom, wandering as his father once had. The Mughal empire, it seemed, had been completely lost, less than a decade after Babur’s death.

The Refugee Prince

So it was that Humayun began his long exile. He sought refuge in the kingdom of Sindh, whose ruler was called Haider. Haider had no intention to annoy Sher Shah, and refused Humayun asylum as well, but Humayun’s followers loitered in his land anyway, roaming from place to place. Hindal too arrived here – the only one of the brothers to remain loyal following Humayun’s general amnesty. It was during the wanderings in Sindh that Humayun first set his eyes upon his future queen consort, Hamida Banu Begum. Hamida would outlive Humayun by decades, and would become one of the most powerful women in Asia as the mother of the mighty Akbar and a shrewd political operator in her own right, but at the time she was only 15 years old. Gulbadan Begum says after that after rejecting Humayun’s proposals for forty days -needless to say, an opium befuddled young king without a kingdom would hardly have seemed a good prospect – she finally relented to marry him.

Hindal himself strongly protested the match, and threatened to withdraw his support if the marriage went ahead – leading many to suggest was in love on Hamida Banu himself. Gulbadan Begum, who would become close friends with Hamida, in fact writes that Hamida had often been seen in Hindal’s apartments. Others say Hindal was simply exasperated by his older brother, who had picked this desperate time to chase after a girl than plan his return to the throne. What was the reason however for Humayun’s sudden desire, in the midst of this desperate fight for his life, to get married, at the cost of his relationship with his only loyal brother?. It may have been lust for a teenage girl, but knowing Humayun, it very well could have been the mandate of his stars.. It cannot be a coincidence that Hamida Banu was a direct descendant of Sheikh Ahmad-e-Jami, a very famous 12th century Shia holy man from Persia known as the ‘His Reverence the Colossal Elephant’, with whom Humayun had a well-documeted obsession What we know for certain is that Humayun insisted on getting married on a specific date personally calculated using his astrolabe,. Hindal gathered his men and departed in a huff, depriving Humayun of one his last sources of support.

Here began the most dangerous parts of Humayun’s journey, through the ‘waterless wastes’ of the Thar desert with his young wife and a handful of men. This involved passing through the lands of hostile Rajput kings, who would be all too glad to get their hands on the son of Babur. One of them, the Rana of Mewar, offered Humayun sanctuary only to attempt to put him in chains and send him to Sher Shah Suri. Humayun and his party barely learned of the plan in time from a servant girl and escaped the Rana’s armies. Another, the raja of Jaisalmer, furiously pursued them, sanding over wells. Villages denied them entry, and soon Humayun’s company, reduced to eating berries, began to dwindle, through starvation and mass desertion. At one point, Humayun had to physically chase after two formerly loyal generals when they tried to escape at night and plead with them piteously to stay. Gulbadan writes that Humayun confessed to her once that his lowest point was when his men rudely refused to lend his heavily pregnant young wife Hamida one of their horses to ride after the queen’s horse collapsed. He had to give up his own horse, and ride behind his own men on a camel. She also recounts Hamida never forgetting having to kill their horses for food, and eating the boiled meat in soldiers helmets for want of bowls

When finally offered asylum by the Rajput ruler of Amarkot, Rana Prasad, the once mighty Mughal emperor had only seven horsemen in attendance on him. He would sheepishly have to confess to the Rana that he had no precious gifts to give him befitting of his station. The Hindu nobleman seems to have taken pity on Humayun, and allowed him to stay for months, emptying a fort for his residence and even providing him with some soldiers and a personal guard .It was during this dark time that, Gulbadan reports, Humayun bounded his household one morning and announced that he had a dream where he had been visited by a “venerable man dressed from head to foot in green”, whose faced burned with light. This man had declared himself none other than His Reverence the Colossal Elephant. A mighty son would be born to Humayun, the Colossal Elephant had propehesised,and then he whispered to Humayun in his dream the heaven’s chosen name for the boy.

Soon after this, at Amarkot, on a night in October ‘with the moon in Leo” Hamida gave birth to Humayun’s long sought after son, whom he would give the name from his dream – Akbar. The impoverished King celebrated the news of Akbar’s birth by breaking a pod of musk in a china bowl, enveloping the room in a rich fragrance, and distributing the pieces amongst his men “This is the only present I can afford to make you on the birth of my son, whose fame will one day spread around the world like this fragrance has spread around this room”

Humayun would soon have to leave Amarkot. For a time it seemed his fortunes were looking up, for along with the troops provided by Rana Prasad, he managed to gather some local tribesmen to him as well as some Rajput warriors, He was even rejoined by Bairam Khan, an old general and friend of his fathers, who had been captured by Sher Shah three years ago but escaped his dungeons. Askari however rode out with a large army to stomp this out, having promised Kamran Humayun’s head. Humayun’s small warband crumbled. Humayun and Hamida, with Bairam Khan’s help, escaped into the Hindukush mountains,but they had to leave their infant son Akbar behind. Akbar fell into Askari’s hands, and spent the first years of his childhood in the court of his father’s most determined enemy, Kamran. Thankfully, the baby had his eleven milk mothers, women from noble families personally chosen by Hamida to nurse the boy, who had elected to stay back with Akbar. Being too well connected to be disposed of without scandal, these ladies, amongst whom were many future grand dames of the Mughal empire such as Maham and Jiji Ananga, formed a fiercely protective ring about the abandoned baby, safeguarding him from harm until Humayun returned.

Humayun and Hamida, bereft at the loss of their son, fled to the court of the Shah of Persia, Shah Tamasp.

They spent the next few years there as distinguished refugees, a fixture in public feasts and dinner parties, constantly petitioning the Shah to help them reclaim their lost lands. The Shah eventually received them in full honours, but as a condition of receiving asylum in Persia, Humayun had to go through the further humiliation of publicly rejecting his Sunni faith and converting to Shia Islam. He also cant have been very heartened by the fact that the Persian Shah met with Sher Shah and Kamran’s ambassadors as well, sent there to persuade the Shah to hand over the false king Humayun. In the end, the Persian Shah was persuaded to support Humayun and Hamida by his sister, Shehzada Sultan, who had taken a liking to the pleasant, down on their luck couple.

The Shah eventually granted Humayun an army of 12,000 men, on the condition that he first use the army to conquer Kandahar and give it to the Persians, after which he could do with them as he willed. After a long siege, Humayun with the help of the experienced, swashbuckling Bairam Khan, captured Kandahar from Askari and marched on his brother Kamran in Kabul. Kamran’s rule in Kabul had been oppressive and tyrannical, and his men promptly defected to Humayun as he approached the city. Humayun finally defeated Kamran and was united with his now three year old son, whom he handed over to his weeping mother..

Restoration

Humayun was determined to show that he had learned from his mistakes and initially made a show of ruthlessness, killing Kamran’s supporters and having his prodigal brother bought to him in chains. However, when Kamran was brought before him, he took a whip from one of Humayun’s courtiers and put it around his own neck, and prostrated himself before Humayun like a common criminal. This was enough to break the soft hearted Humayun who exclaimed ‘there is no need for this,’, strode up to his brother and embraced him and in the words of Abu Fazl ‘wept so violently that all those who were present were touched in the heart”. He had Kamran sit beside him and share a glass of sherbert with him, and unbelievably, pardoned Kamran again. He also eventually reconciled with his other brothers.

Hindal would now remain loyal to Humayun to the end of his life, perhaps having time to gain some perspective in the years after the Hamida affair, where he had given up politics and wandered the wilds as a dervish. Kamran and Askari however were soon up to their old tricks, and within the year had raised armies again in rebellion. Though Askari would be defeated and sent packing into exile, Kamran spent eight years plundering and ravaging Humayun’s lands, even briefly recapturing Kabul twice. Hindal would be killed by Kamran during one of these skirmishes. When Kamran was finally captured,trying to escape Humayun’s men disguised in a woman’s burqah, Humayun’s courtiers all now insisted that the enemy of the state must be put to death, or Humayun would be forsaking his kingly duties.

“Brotherly custom has nothing to do with ruling” Gulbadan quotes his advisors as saying “if you wish to be a good brother, then give up your throne”.

Humayun could not bring himself to do it, but ultimately was persuaded to have Kamran blinded and sent into exile to Mecca. Jauhar, who had been ordered to massage Kamran the night before his punishment, personally witnessed the ‘light of his eyes’ being extinguished and writes that Humayun’s grief was so great that he had sent Jauhar away from his presence. The blinded Kamran went into quiet exile in Mecca, disappearing from history.

Humayun gathered his strength for almost a decade in Kabul, raising his son Akbar, Back in his abandoned lands in India, the stars he worshipped finally began coming through for him. The indomitable Sher Shah, by all accounts a just and competent ruler, came to an untimely end when a cannon exploded in his face while he was inspecting it. His son died a few years later campaigning against Rajputs, and Bahadur Shah of Gujarat was killed in a shoot out during a harebrained scheme to kidnap and ransom a Portuguese Governor. So it was that Humayun, in 1555, fifteen years after he had been chased away by Sher Shah, re-crossed the Indus which just three thousand men. On the banks of the Indus, Humayun had the twelve year old Akbar bathed and brought before him, and under a crescent moon, recited some verses of the Quran, and with each verse breathed on the prince, an old Turko-Mongol way of conferring his blessings, and was “so delighted and happy, that it could be said that he attained all the blessing of this world and the next”. Within months, Humayun troops marched into Delhi .

He did not have long to enjoy his victory. A winter night after his reconquest, he climbed to the roof of the Sher Mandal in Delhi to observe the rising of Venus. On his way back down, he tripped on his long fur robe, and fell down the stairs, hitting his temple and falling unconscious. In three days, he was dead. It had only been six months since he had regained Delhi.

Bairam Khan thundered on his horse to the camp of the thirteen year old Akbar, where he hastily oversaw the princes crowning, but already, the warlords of northern India began sharpening their weapons, sensing the barely re-established Mughal empire was up for grabs. No one would have guessed that this terrified child would have an uninterrupted rule of fifty years and leave the empire incomparably richer than he had found it. But that is another story.

For all his faults – his lack of urgency and ambition, his almost naive soft heartedness, his predilection for opium- Humayun ultimately suffered because he was a gentle man in an age of war. One of our last accounts of him was from the journal of a Turkish Admiral, Sidi Rais, who visited Humayun’s court in the final year of his life, and observed the King engaged in his favourite activities – lying down plans for new astronomical observatories and setting up a huge library. When Rais called his master the Ottoman sultan the greatest emperor since Alexander, Humayun replied “surely no other man is worthy to bear the title of king than the sultan of Turkey, him alone in this world”. Whether humility or a gentle jab, no king anywhere at the time would have tolerated even in jest being compared unfavourably to another, and Sidi Rais sneeringly reports this unkingly humility as proof of the emperors weakness. To modern readers though, Humayun’s self-effacing nature is far more endearing than the self aggrandising bombast of his contemporary peers.

It is common to hear stories of kings who gained kingdoms by murdering their brothers, but rarer to hear a story of kings who lost their kingdoms by refusing to do so. Yet, Humayun in spite of everything persevered, and regained his home on his own terms, and set the foundation on which his son would build an empire. He was buried in his chosen homeland, far from the Steppes of his ancestors, and lies there still , in his cold marble tomb amidst the bustling streets of Old Delhi. Hamida is buried there as well, as are many of their famous descendants, and for now, the government of India still protects and safeguards their resting place. With the rewriting of history to wipe the Mughals names from our past, one can only hope that he is not made an exile once again in his afterlife, though it would be a fate one would imagine he would bear with equanimity.

Amazingly well written..Even though I love history I have never had an opportunity to read and learn about Humayun in such depths.. it kept me enthralled. It is a well researched blog and gives so much information that ordinary history books do not… it was great to learn so much about Humayun who I have known only as Akbar’s father.. Excellent and exceptional read and style of writing… looking forward to many more such blogs…

Thank you! I had fun writing it.

This piece does a fantastic job of combining solid research with a simple, engaging writing style. The use of little-known facts keeps the reader curious and eager to learn more. It’s refreshing to see complex information presented in a way that’s easy to understand without feeling watered down. The surprising details sprinkled throughout not only inform but also entertain—making it a memorable read.